Brain Imaging Data Analysis Workflows: A Comprehensive Guide from Foundations to AI

This article provides a comprehensive guide to modern brain imaging data analysis workflows, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Brain Imaging Data Analysis Workflows: A Comprehensive Guide from Foundations to AI

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to modern brain imaging data analysis workflows, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It covers the foundational principles of data organization and standardization, explores both established and emerging AI-driven methodological approaches, addresses critical troubleshooting and optimization challenges in large-scale analysis, and outlines best practices for validation and reproducibility. By synthesizing current tools, standards, and computational strategies, this resource aims to equip practitioners with the knowledge to build robust, efficient, and clinically translatable neuroimaging pipelines.

Laying the Groundwork: Core Concepts and Data Standards in Neuroimaging

Neuroimaging experiments generate complex data that can be arranged in numerous ways. Historically, the absence of a consensus on how to organize and share this data has led to significant inefficiencies in neuroscience research. Even researchers within the same laboratory often opted to arrange their data differently, leading to misunderstandings and substantial time wasted on rearranging data or rewriting scripts to accommodate varying structures [1] [2]. This lack of standardization constitutes a major vulnerability in the effort to create reproducible, automated workflows for neuroimaging data analysis [3]. The Brain Imaging Data Structure (BIDS) was developed to address this critical need, providing a simple, easy-to-adopt standard for organizing neuroimaging and associated behavioral data [1]. By formalizing file and directory structures and specifying metadata files using controlled vocabulary, BIDS enables researchers to overcome the challenges of data heterogeneity and ensure the reliability of their analytical workflows [4].

BIDS Fundamentals: Core Principles and Structure

Organizational Philosophy and Design

BIDS is a community-driven standard that describes a formalized system for organizing, annotating, and describing data collected during neuroimaging experiments [4]. Its design is intentionally based on simple file formats and folder structures to reflect current laboratory practices, making it accessible to scientists from diverse backgrounds [1]. The core organizational principles of BIDS can be summarized as follows: using NIFTI files as the primary imaging format, accompanying key data with JSON sidecar files that provide parameters and descriptions, and employing a consistent folder structure and file naming convention as prescribed by the specification [5]. This structure is platform-independent and designed to be both intuitive and comprehensive, covering most common experimental designs while remaining adaptable to new modalities through a well-defined extension process [1] [2].

Directory and File Structure

The BIDS directory structure follows a consistent hierarchical pattern that organizes data by subjects, optional sessions, and data modalities. The general hierarchy is as follows: sub-<participant_label>[/ses-<session_label>]/<data_type>/ [5]. Key directories include anat for anatomical data, func for functional data, dwi for diffusion-weighted imaging, fmap for field maps, and beh for behavioral data. Additional directories such as code/, derivatives/, stimuli/, and sourcedata/ may be included for specialized purposes [5].

Table 1: Core BIDS Directory Structure

| Directory | Content Description | Example Files |

|---|---|---|

sub-<label> |

Participant-specific data | All data for a single participant |

ses-<label> |

Session-specific data (optional) | Data for different time points |

anat/ |

Anatomical imaging data | sub-01_T1w.nii.gz, sub-01_T1w.json |

func/ |

Functional MRI data | sub-01_task-nback_bold.nii.gz, sub-01_task-nback_events.tsv |

dwi/ |

Diffusion-weighted imaging | sub-01_dwi.nii.gz, sub-01_dwi.bval, sub-01_dwi.bvec |

fmap/ |

Field mapping data | sub-01_phasediff.nii.gz, sub-01_phasediff.json |

beh/ |

Behavioral data | Task performance data, responses |

File naming in BIDS follows a strict convention based on key-value pairs (entities) that establish a common order within a filename [5]. For instance, a filename like sub-01_ses-pre_task-nback_bold.nii.gz immediately conveys that this is the functional MRI data for subject 01 during a pre-intervention session performing an n-back task. This systematic approach ensures that both humans and software tools can readily parse the content and context of each file without additional documentation.

The BIDS Ecosystem: Tools and Applications

The BIDS specification is supported by a rich ecosystem of software tools and resources that enhance its utility and adoption. This ecosystem includes the core specification with detailed implementation guidelines, the starter kit with simplified explanations for new users, the BIDS Validator for automatically checking dataset integrity, and BIDS Apps—a collection of portable pipelines that understand BIDS datasets [1]. A growing number of data analysis software packages can natively understand data organized according to BIDS, and databases such as OpenNeuro.org, LORIS, COINS, XNAT, and SciTran accept and export datasets organized according to the standard [1] [2].

BIDS Validator and Quality Assurance

The BIDS Validator is a critical tool that checks dataset integrity and helps users easily identify missing values or specification violations [1] [2]. This tool is available both as a command-line application and through a web interface, allowing researchers to validate their data organization before analysis or sharing. The validator checks all aspects of a BIDS dataset, including file structure, required files, metadata completeness, and consistency across participants and sessions. For large-scale datasets, tools like CuBIDS (Curation of BIDS) provide robust, scalable implementations of BIDS validation that can be applied to arbitrarily-sized datasets [3].

BIDS Apps and Processing Pipelines

BIDS Apps are containerized data processing pipelines that understand BIDS-formatted datasets [3]. These portable pipelines—such as fMRIPrep for functional MRI preprocessing and QSIPrep for diffusion-weighted imaging data—flexibly build workflows based on the metadata encountered in a dataset [3]. This approach enables reproducible analyses across different computing environments and facilitates the application of standardized preprocessing methods across studies. However, this workflow construction structure can also represent a vulnerability: if the BIDS metadata is inaccurate, a BIDS App may build an inappropriate (but technically "correct") preprocessing pipeline [3]. For example, a fieldmap with no IntendedFor field specified in its JSON sidecar will cause pipelines to skip distortion correction without generating errors or warnings [3].

Table 2: Essential BIDS Tools and Resources

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| BIDS Validator | Validation Tool | Checks dataset integrity and compliance with BIDS specification |

| BIDS Starter Kit | Educational Resource | Simple explanation of how to work with BIDS |

| BIDS Apps | Processing Pipelines | Portable pipelines (fMRIPrep, QSIPrep) that understand BIDS data |

| CuBIDS | Curation Tool | Helps users validate and manage curation of large neuroimaging datasets |

| OpenNeuro | Data Repository | Public database for BIDS-formatted datasets |

| PyBIDS | Python Library | Python library for querying and manipulating BIDS datasets |

BIDS Extension Proposals: Expanding the Standard

The BIDS specification is designed to evolve over time through a backwards-compatible extension process. This is accomplished through community-driven BIDS Extension Proposals (BEPs), which allow the standard to incorporate new imaging modalities and data types [2] [4]. Since its initial focus on MRI, BIDS has been extended to numerous other modalities through this process, including MEG, EEG, intracranial EEG (iEEG), positron emission tomography (PET), microscopy, quantitative MRI (qMRI), arterial spin labeling (ASL), near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS), and motion data [2] [4] [6].

The Motion-BIDS extension exemplifies this adaptive process, addressing the need to organize motion data recorded alongside human brain imaging and electrophysiological data [6]. Motion data is increasingly important in human behavioral research, with biomechanical features providing insights into underlying cognitive processes and possessing diagnostic value [6]. For instance, step length is related to Parkinson's disease severity, and cognitive impairment in older adults is associated with gait slowing [6]. Motion-BIDS standardizes the organization of this diverse data type, promoting findable, accessible, interoperable, and reusable (FAIR) data sharing and Open Science in human motion research [6].

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Dataset Curation Protocol Using CuBIDS

For researchers working with large-scale, heterogeneous neuroimaging datasets, the CuBIDS (Curation of BIDS) package provides an intuitive workflow that helps users validate and manage the curation of their datasets [3]. CuBIDS includes a robust implementation of BIDS validation that scales to large samples and incorporates DataLad—a version control software package for data—as an optional dependency to ensure reproducibility and provenance tracking throughout the entire curation process [3]. The CuBIDS workflow involves several key steps:

- Initial Validation: Run

cubids-validateon the BIDS dataset to identify compliance issues. - Metadata Enhancement: Use

cubids-add-nifti-infoto extract and add crucial information from NIfTI headers to the corresponding JSON sidecars. - Acquisition Grouping: Execute

cubids-groupto identify unique combinations of imaging parameters in the dataset. - Targeted Curation: Use the grouping information to identify and correct metadata inconsistencies across participants.

- Provenance Tracking: Optionally use the

--use-dataladflag to implement reproducible version control throughout curation.

This protocol is particularly valuable for large, multi-site studies where hidden variability in metadata is difficult to detect and classify manually [3]. CuBIDS provides tools to help users perform quality control on their images' metadata and execute BIDS Apps on a subset of participants that represent the full range of acquisition parameters present in the complete dataset, dramatically accelerating pipeline testing [3].

BIDS Conversion Protocol

Converting raw neuroimaging data to BIDS format follows a standardized protocol:

- DICOM to NIfTI Conversion: Use tools like dcm2niix to convert raw DICOM files to NIfTI format.

- File Organization: Arrange NIfTI files according to BIDS directory structure (sub-

- Sidecar Creation: Generate JSON sidecar files containing relevant metadata for each imaging file.

- Tabular Data Preparation: Create participants.tsv, sessions.tsv (if multi-session), and other required tabular files.

- Dataset Description: Create dataset_description.json with mandatory fields (Name, BIDSVersion, DatasetType).

- Validation: Run the BIDS Validator to identify and correct any compliance issues.

This protocol ensures that data is organized consistently, facilitating subsequent analysis and sharing.

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Tools for BIDS Workflows

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for BIDS Experiments

| Tool/Reagent | Function/Purpose | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| dcm2niix | DICOM to NIfTI Converter | Converts raw scanner DICOM files to BIDS-compliant NIfTI format |

| BIDS Validator | Dataset Compliance Checker | Validates BIDS dataset integrity before analysis or sharing |

| CuBIDS | Large Dataset Curation | Manages metadata curation for large, heterogeneous datasets |

| BIDS Apps | Containerized Processing Pipelines | Executes reproducible analyses (fMRIPrep, QSIPrep) on BIDS data |

| PyBIDS | Python API for BIDS | Queries and manipulates BIDS datasets programmatically |

| JSON Sidecars | Metadata Storage | Contains key parameters and descriptions for associated imaging data |

| DataLad | Version Control System | Tracks changes and ensures reproducibility throughout curation |

Benefits and Impact of BIDS Adoption

The adoption of BIDS provides significant benefits both for the broader scientific community and for individual researchers. For the public good, BIDS lowers scientific waste, provides opportunities for less-funded researchers, improves efficiency, and spurs innovation [1]. For individual researchers, BIDS enables and simplifies collaboration, as reviewers and funding agencies increasingly value reproducible results [1]. Furthermore, researchers who use BIDS position themselves to take advantage of open-science based funding opportunities and awards [1].

From a practical perspective, BIDS benefits researchers in several concrete ways: it becomes easier for collaborators to work with your data, as they only need to be referred to the BIDS specification to understand the organization; a growing number of data analysis software packages natively understand BIDS-formatted data; and public databases will accept datasets organized according to BIDS, speeding up the curation process if you plan to share your data publicly [1] [2]. Perhaps most importantly, using BIDS ensures that you—as the likely future user of the data and analysis pipelines you develop—will be able to understand and efficiently reuse your own data long after the original collection [1].

The Brain Imaging Data Structure addresses a critical need in modern neuroscience by providing a standardized framework for organizing, describing, and sharing neuroimaging data. By adopting simple file formats and directory structures that reflect current laboratory practices, BIDS has created an accessible yet powerful standard that promotes reproducibility, facilitates collaboration, and enhances the efficiency of neuroimaging research. The growing ecosystem of BIDS-compliant tools and databases, coupled with the community-driven extension process, ensures that the standard will continue to evolve to meet emerging needs in neuroscience and related fields. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals working with brain imaging data, adopting BIDS represents a fundamental step toward ensuring the reliability, reproducibility, and shareability of their research outputs.

The complexity of the brain necessitates the use of diverse, non-invasive neuroimaging technologies to capture its structural architecture, functional dynamics, and intricate connectivity. No single modality can fully elucidate the brain's workings; instead, a multimodal approach that integrates complementary data is paramount for a holistic understanding [7]. Structural MRI (sMRI) provides a high-resolution anatomical blueprint, while functional MRI (fMRI) maps cognitive processes through hemodynamic changes. Diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) traces the white matter pathways that connect distant brain regions. In contrast, Electroencephalography (EEG) and Magnetoencephalography (MEG) offer a direct, millisecond-resolution view of neural electrical activity. This Application Note details the essential technical specifications, experimental protocols, and integrated applications of these core modalities, framing them within advanced brain imaging data analysis workflows critical for both basic research and drug development.

Modality Specifications and Comparative Analysis

Table 1: Technical Specifications and Primary Applications of Core Neuroimaging Modalities

| Modality | Spatial Resolution | Temporal Resolution | What It Measures | Primary Applications | Key Advantages | Principal Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| sMRI | Sub-millimeter | Minutes | Brain anatomy (grey/white matter volume, cortical thickness) | Anatomical reference, morphometry, tracking neurodegeneration | High spatial detail, excellent soft-tissue contrast | No direct functional information, slow acquisition |

| fMRI | 1-3 mm | 1-2 seconds | Blood-oxygen-level-dependent (BOLD) signal (indirect correlate of neural activity) | Functional connectivity, localization of cognitive tasks, network dynamics | Widespread availability, good spatial resolution for whole-brain coverage | Indirect and slow measure of neural activity, sensitive to motion |

| DWI | 2-3 mm | Minutes | Directionality of water molecule diffusion (white matter tract integrity) | Structural connectivity, tractography, assessing white matter integrity | Unique insight into structural brain networks | Inferior spatial resolution vs. sMRI, complex modeling |

| EEG | >10 mm (poor) | <1 millisecond | Electrical potential on scalp from synchronized postsynaptic currents | Brain dynamics, neural oscillations, event-related potentials, clinical monitoring | Excellent temporal resolution, portable, low cost | Poor spatial resolution, sensitive to non-neural artifacts |

| MEG | 3-5 mm (good with modeling) | <1 millisecond | Magnetic field on scalp from synchronized postsynaptic currents | Source localization of neural activity, brain dynamics, connectivity | Excellent temporal and good spatial resolution for source modeling | Extremely expensive, non-portable, insensitive to radial sources |

Table 2: Quantitative Performance in Benchmarking Studies

| Study Context | Modality/Comparison | Key Quantitative Finding | Implication for Workflow Design |

|---|---|---|---|

| Source Localization Accuracy [8] [9] | MEG alone | Higher accuracy for superficial, tangential sources | Optimal for sulcal activity |

| EEG alone | Higher accuracy for radial sources | Optimal for gyral activity | |

| MEG + EEG Combined | Consistently smaller localization errors vs. either alone | Multimodal integration significantly improves spatial precision | |

| Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) Classification [10] | 306-channel MEG | 73.2% average accuracy (1-second trials) | Benchmark for high-fidelity target detection |

| 64-channel EEG | 69% average accuracy | Good performance with high-density setup | |

| 9-channel EEG | 66% average accuracy | Usable BCI with optimized, portable setup | |

| 3-channel EEG | 61% average accuracy | Performance degrades but remains above chance | |

| Pharmacodynamic Biomarker Development [11] | fMRI, EEG, PET | Identifies four key questions for clinical trials: brain penetration, target engagement, dose selection, indication selection | Provides a structured framework for de-risking drug development |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Combined MEG and EEG for High-Fidelity Source Localization

This protocol is designed to capitalize on the complementary strengths of MEG and EEG to achieve superior spatiotemporal resolution in localizing neural activity [8] [9].

1. Experimental Design and Stimulation:

- Stimuli: Use focal, well-controlled stimuli (e.g., Gabor patches for visual cortex) that can evoke robust, localizable neural responses.

- Paradigm: Employ an event-related design. Present stimuli for 500 ms with a randomized inter-stimulus interval (e.g., 1-6.5 seconds) to facilitate deconvolution of the neural response.

- Task: Incorporate a behavioral task (e.g., fixation cross change detection) to ensure participant alertness and monitor performance. Discard trials with incorrect behavioral responses.

2. Simultaneous Data Acquisition:

- MEG: Record using a whole-head system (e.g., 306-channel Elekta Neuromag or CTF system). Sample data at a minimum of 1000 Hz. Ensure the subject's head position is monitored and corrected if necessary.

- EEG: Record simultaneously using a 64+ channel cap. Sync EEG and MEG acquisition systems using a shared trigger pulse. Use appropriate reference and ground electrode placements.

- Ancillary Data: Record the subject's head shape (via digitization) and the location of EEG electrodes relative to MEG head position indicators (HPIs) for co-registration.

3. Structural MRI Co-registration:

- Acquire a high-resolution T1-weighted sMRI scan for each subject.

- Co-register the MEG/EEG sensor data to the subject's anatomical MRI using the digitized head points and fiducial markers (nasion, left/right pre-auricular points).

4. Data Preprocessing:

- Filter data (e.g., 0.1-40 Hz bandpass for evoked responses).

- Apply artifact correction (e.g., Signal-Space Separation (SSS) for MEG; ICA for ocular and cardiac artifacts in EEG).

- Epoch data into trials time-locked to stimulus onset.

5. Source Estimation and Analysis:

- Construct a forward model using a boundary element model (BEM) based on the sMRI.

- Calculate an inverse solution (e.g., depth-weighted minimum-norm estimate (MNE) or dynamic statistical parametric mapping (dSPM)) using the combined MEG+EEG data.

- Compare the localization results against a ground truth, such as BOLD fMRI activation from an identical task, to validate accuracy.

Protocol: Integrating Neuroimaging in CNS Drug Development

This protocol outlines a precision medicine approach, using neuroimaging biomarkers to stratify patients and measure drug effects, thereby de-risking clinical trials [11].

1. Pre-Clinical and Phase 1: Establishing Target Engagement

- Objective: Determine if the drug candidate engages the intended brain target and produces a measurable functional effect.

- Modality: fMRI or task-based EEG/MEG.

- Design: Double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover or parallel-group study.

- Procedure:

- Administer the drug or placebo.

- During expected peak plasma concentration, scan participants while they perform a cognitive task known to engage the target neural circuit.

- Analysis: Compare the neural activity (e.g., BOLD signal in a specific region, or EEG/MEG oscillatory power) between drug and placebo conditions. A significant difference confirms functional target engagement.

2. Phase 2: Patient Stratification and Dose-Finding

- Objective: Identify a biomarker that predicts clinical response and determine the optimal dose.

- Modality: Accessible and scalable modalities like EEG are preferred for larger trials.

- Design: Large, biomarker-stratified design.

- Procedure:

- At baseline, collect neuroimaging data (e.g., resting-state EEG) from all patients.

- Use a pre-defined biomarker signature (e.g., a specific EEG pattern) to stratify patients into "biomarker-positive" and "biomarker-negative" subgroups.

- Randomize patients to different dose groups or placebo.

- Analysis: Test the primary clinical outcome. The hypothesis is that the "biomarker-positive" subgroup will show a significantly better response to the drug compared to the "biomarker-negative" subgroup and placebo, demonstrating predictive validity.

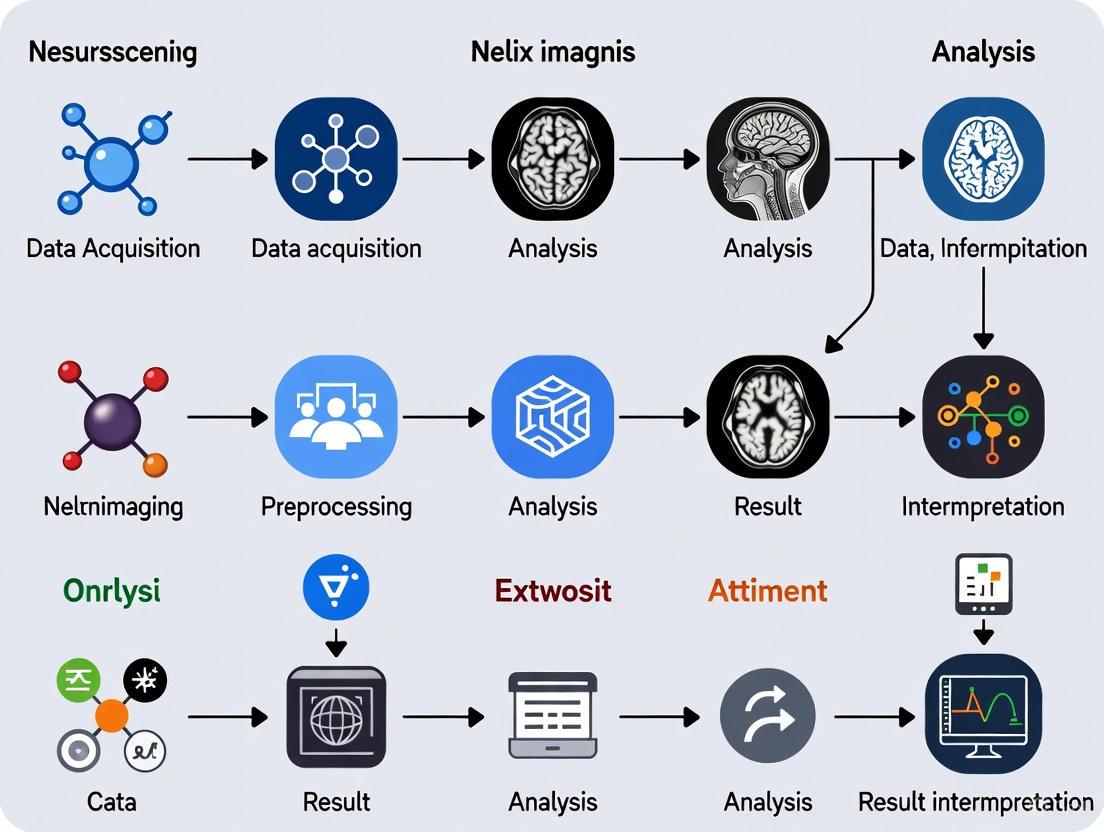

Visual Workflows and Signaling Pathways

Diagram 1: Multimodal Neuroimaging Data Analysis Workflow. This workflow integrates structural, functional, and electrophysiological data to produce validated biomarkers and insights.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Resources for Multimodal Neuroimaging Research

| Resource Category | Specific Examples & Functions | Relevance to Workflows |

|---|---|---|

| Public Data Repositories | Human Connectome Project (HCP) Data [7]: Provides pre-processed, high-quality multimodal data (fMRI, sMRI, DWI) for method development and testing. | Essential for benchmarking algorithms and accessing large-scale normative datasets. |

| Analysis Software & Platforms | FSFreeSurfer, FSL, SPM, MNE-Python, Connectome Workbench: Open-source suites for structural segmentation, functional and diffusion analysis, and MEG/EEG source estimation. | Form the core of the analytical pipeline; interoperability is key for multimodal integration. |

| Computational Frameworks | Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) [7]: Framework for analyzing brain connectivity data represented as graphs, enabling multimodal fusion and prediction. | Represents the cutting-edge for integrating structural and functional connectivity features. |

| Biomarker Platforms (Industry) | Alto Neuroscience Platform [11]: Uses EEG and other biomarkers to stratify patients in clinical trials for psychiatric disorders, validating the "precision psychiatry" approach. | Provides a commercial and clinical validation of the protocols described herein. |

| Experimental Stimuli | Natural Object Dataset (NOD) [12]: A large-scale dataset containing fMRI, MEG, and EEG responses to naturalistic images, enabling ecologically valid studies of object recognition. | Critical for experiments aiming to move beyond simple, controlled stimuli to understand brain function in natural contexts. |

The expansion of large-scale, centralized biomedical data resources has fundamentally altered the landscape of neuroimaging research, enabling unprecedented discoveries in brain structure, function, and disease. These repositories provide researchers with the extensive datasets necessary to develop and validate robust computational models, moving beyond underpowered studies towards reproducible neuroscience. For researchers and drug development professionals, navigating the specific characteristics, access procedures, and optimal use cases of these resources is a critical first step in designing effective analysis workflows. This guide provides a detailed comparison and protocols for four pivotal resources: UK Biobank, ABCD Study, OpenNeuro, and ADNI, framing their use within a comprehensive brain imaging data analysis pipeline.

Resource Comparison and Characterization

The major data resources cater to distinct research populations, data types, and primary objectives. The table below provides a systematic comparison of their core attributes for researcher evaluation.

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Centralized Neuroimaging Data Resources

| Resource | Primary Focus & Population | Key Data Modalities | Access Model & Cost | Sample Scale & Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UK Biobank [13] | Longitudinal health of 500,000 UK participants; general population, adult (aged 40-69 at recruitment) [13] | Multi-modal imaging, genomics, metabolomics, proteomics, healthcare records, wearable activity [13] [14] [15] | Approved researchers; access fee for international researchers [13] | ~500,000 participants; Imaging for 100,000+ [13] [15]; Most comprehensive phenotypic data |

| ABCD Study [16] | Brain development and child health in the US; over 10,000 children aged 9-10 at baseline | Brain imaging (fMRI, sMRI), neurocognitive assessments, biospecimens, substance use surveys | Controlled access; no cost; requires Data Use Certification (DUC) [16] | ~10,000+ participants; Longitudinal design through adolescence |

| OpenNeuro [17] [18] | Open platform for sharing any neuroimaging dataset; diverse populations and focuses | Brain imaging data (BIDS-formatted), often with behavioral phenotypes | Open access for public datasets; free download and upload [18] | 1,000+ datasets; Platform for data sharing; No central cohort |

| ADNI [19] [20] | Alzheimer's Disease (AD) progression; older adults with Normal Cognition, MCI, and AD | Longitudinal MRI, PET, genetic data, cognitive tests, biomarkers (e.g., CSF, plasma) | Controlled access; application required; no cost for approved research [20] | ~2,000+ participants; Deeply phenotyped for neurodegenerative disease |

Data Access Protocols and Workflows

Gaining access to these resources involves navigating specific, and often mandatory, procedural pathways. The following protocols detail the steps for each.

UK Biobank Access Protocol

- Registration and Application: Researchers must register on the UK Biobank access management system and submit a detailed application outlining their research purpose, the specific data fields required, and the intended use [13].

- Approval and Costing: Applications are reviewed by the UK Biobank team. Upon approval, the researcher or their institution is invoiced for the data access fee, which contributes to the maintenance and expansion of the resource [13].

- Data Access: Once access is granted, researchers can download the data directly or, increasingly, analyze it in-place using the UK Biobank's Research Analysis Platform (UKB-RAP) to avoid transferring large datasets [13].

ABCD Study & ADNI Access Protocol

The ABCD Study and ADNI share a similar controlled-access model, governed by NIH policies.

- Data Use Agreement (DUA): The principal investigator must read and agree to the resource-specific Data Use Agreement, which outlines terms of use, data security requirements, and publication policies [16] [20].

- Online Application: The researcher must complete an online application form via the respective data hub:

- Review and Approval: The respective data sharing committee (e.g., ADNI's Data Sharing and Publications Committee) reviews applications, typically within two weeks [20].

- NIH Security Compliance: Approved users must comply with NIH Security Best Practices for controlled-access data, which often entails using institutional IT systems or cloud providers meeting specific security standards like NIST SP 800-171 [16].

- Account Maintenance: A provision of the access agreement is the submission of an annual update to maintain an active account [20].

OpenNeuro Data Access and Sharing Protocol

As an open-data platform, OpenNeuro simplifies data sharing and retrieval.

- Downloading Public Data: Users can search and download any publicly available dataset directly through the web interface or via the command-line interface (CLI) without any access application [18].

- Uploading Data: Researchers preparing to share data must format their dataset according to the Brain Imaging Data Structure (BIDS) standard. The platform runs the BIDS-validator automatically upon upload to ensure compliance [17].

The following workflow diagram summarizes the access pathways for these resources.

Experimental Design and Analytical Protocols

Leveraging these datasets requires careful experimental design. A recent study on brain-age prediction using multi-head self-attention models provides a concrete example of a cross-dataset analytical workflow [21].

Case Study: Brain Age Prediction Model

Objective: To develop a lightweight, accurate deep learning model for brain age estimation and evaluate its generalizability and potential bias across Western and Middle Eastern populations [21].

Datasets and Harmonization:

- Primary Training/Testing Data: 4,635 healthy individuals (aged 40-80) from Western datasets: ADNI, OASIS-3, Cam-CAN, and IXI [21].

- External Validation Data: 107 subjects from a Middle Eastern (ME) dataset (Tehran, Iran) [21].

- Data Split: 80% of the Western data (n=3,700) for training, 20% (n=935) for testing [21].

Model Architecture:

- Base Network: 3D Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) for feature extraction from structural MRI.

- Core Innovation: Integration of multi-head self-attention mechanisms to capture long-range spatial dependencies in brain images, enhancing feature learning.

- Efficiency: Model designed to be lightweight with approximately 3 million parameters [21].

Performance and Bias Analysis:

- Evaluation Metric: Mean Absolute Error (MAE) between predicted brain age and chronological age.

- Bias Correction: Application of a post-hoc linear regression correction (Y = aX + b) fitted on the Western training set to adjust predictions on the test sets [21].

Table 2: Brain Age Prediction Model Performance Across Datasets [21]

| Dataset | Number of Subjects (N) | Mean Age (Std) | MAE before Bias Correction (Years) | MAE after Bias Correction (Years) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Western Test Set (Total) | 935 | - | 2.09 | 1.99 |

| ADNI | 442 | 71.94 (5.09) | 1.24 | 1.23 |

| OASIS-3 | 348 | 64.60 (8.54) | 1.98 | 2.00 |

| Cam-CAN | 82 | 60.39 (12.17) | 4.30 | 4.43 |

| IXI | 63 | 58.37 (10.13) | 4.23 | 4.04 |

| Middle Eastern (ME) Dataset | 107 | 50.31 (4.76) | 5.83 | 5.96 |

Key Findings: The model achieved state-of-the-art accuracy on the Western test set (MAE = 1.99 years) but performed significantly worse on the Middle Eastern dataset (MAE = 5.83 years). Critically, bias correction based on the Western data further degraded performance on the ME dataset, highlighting profound population-specific differences in brain aging and the risk of bias in models trained on non-diverse data [21].

Protocol for fMRI Study Design: The Scan Time vs. Sample Size Trade-Off

A fundamental design consideration for functional MRI (fMRI) studies is the trade-off between scan time per participant and total sample size, especially under budget constraints. A recent Nature (2025) study provides an evidence-based framework for this optimization [22].

Key Empirical Relationship:

- Prediction accuracy of phenotypes from resting-state fMRI increases with the total scan duration (sample size × scan time per participant) [22].

- For scans ≤20 minutes, sample size and scan time are largely interchangeable; accuracy increases linearly with the logarithm of the total scan duration [22].

- However, diminishing returns are observed for longer scan times, with sample size ultimately being more critical for prediction power [22].

Cost-Efficiency Optimization:

- 10-minute scans are cost-inefficient for achieving high prediction performance [22].

- The most cost-effective scan time is at least 20 minutes, with 30 minutes being optimal on average, yielding ~22% cost savings compared to 10-minute scans [22].

- Overshooting the optimal scan time is cheaper than undershooting it, so a scan time of at least 30 minutes is recommended [22].

The following diagram illustrates the analytical workflow integrating data access, study design, and model validation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Executing a robust neuroimaging data analysis requires a suite of computational tools and platforms that constitute the modern "research reagent."

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Neuroimaging Data Analysis

| Tool / Resource | Primary Function | Application in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| BIDS Validator [17] | Validates compliance of datasets with the Brain Imaging Data Structure standard. | Essential pre-processing step before uploading data to OpenNeuro or other BIDS-compliant platforms. |

| OpenNeuro CLI [18] | A command-line interface for OpenNeuro. | Enables automated and efficient upload/download of large neuroimaging datasets, particularly useful for HPC environments. |

| DataLad & git-annex [17] | Version control and management of large files. | Foundation of OpenNeuro's data handling; allows for precise tracking of dataset revisions and efficient data distribution. |

| UKB-RAP (Research Analysis Platform) [13] | A cloud-based analysis platform provided by UK Biobank. | Allows approved researchers to analyze UK Biobank data in-place without the need for massive local download and storage. |

| NBDC Data Hub [16] | The NIH data ecosystem hosting ABCD and HBCD study data. | The central portal for querying, accessing, and managing controlled-access data from the ABCD study with streamlined Data Use Certification. |

| LONI IDA [20] | The Image and Data Archive for ADNI. | The secure repository where approved researchers access and download ADNI imaging, clinical, and biomarker data. |

Centralized data resources like UK Biobank, ABCD, OpenNeuro, and ADNI are powerful engines for neuroimaging research and drug development. The choice of resource must be guided by the specific research question, considering population focus, data modalities, and scale. As demonstrated, the analytical workflow—from navigating access protocols and optimizing study design to validating models across diverse populations—is critical for generating robust, reproducible, and meaningful scientific insights. The growing emphasis on population diversity and computational efficiency, as seen in the latest studies, will continue to shape the future of brain imaging data analysis.

The advent of large-scale neuroimaging datasets has fundamentally transformed brain imaging research, enabling unprecedented exploration of brain structure, function, and connectivity across diverse populations [23]. Initiatives like the Human Connectome Project, the UK Biobank (with over 50,000 scans), and the Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative have generated petabytes of imaging data, providing researchers with powerful resources for investigating neurological and psychiatric disorders [24] [23]. However, this data deluge presents substantial computational challenges that transcend the capabilities of traditional desktop computing environments. The size, complexity, and multimodal nature of modern neuroimaging data demand sophisticated computing infrastructure and specialized analytical approaches [25] [23].

Cloud and High-Performance Computing (HPC) platforms have emerged as critical infrastructures for managing, processing, and analyzing large-scale neuroimaging data [23]. These platforms provide the necessary computational power, storage solutions, and scalability required for contemporary brain imaging research. The integration of standardized data formats, containerized software solutions, and workflow management systems has further enhanced the reproducibility, efficiency, and accessibility of neuroimaging analyses across diverse computing environments [26] [24] [27]. This article presents application notes and protocols for leveraging cloud and HPC platforms in brain imaging data analysis workflows, with specific methodologies, performance benchmarks, and practical implementation guidelines for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Platform Comparison and Performance Metrics

Quantitative Performance of Scalable Processing Pipelines

Processing pipelines demonstrate significantly different performance characteristics across computing environments. The following table summarizes benchmark results for prominent neuroimaging pipelines evaluated on large datasets:

Table 1: Performance comparison of neuroimaging pipelines on large-scale datasets

| Pipeline | Computing Environment | Sample Size | Processing Time per Subject | Acceleration Factor | Key Innovation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DeepPrep [24] | Local workstation (GPU-equipped) | UK Biobank subset | 31.6 ± 2.4 minutes | 10.1× faster than fMRIPrep | Deep learning integration |

| DeepPrep [24] | HPC cluster (batch processing) | 1,146 participants | 8.8 minutes per subject | 10.4× more efficient than fMRIPrep | Workflow manager (Nextflow) |

| fMRIPrep [24] | Local workstation (CPU) | UK Biobank subset | 318.9 ± 43.2 minutes | Baseline | Conventional algorithms |

| BABS [27] | HPC (Slurm/SGE) | Healthy Brain Network (n=2,565) | Variable (dependent on BIDS App) | N/A (enables reproducibility) | DataLad-based provenance tracking |

DeepPrep demonstrates remarkable computational efficiency, processing the entire UK Biobank neuroimaging dataset (over 54,515 scans) within 6.5 days in an HPC cluster environment [24]. This represents a significant advancement in processing scalability compared to conventional approaches. The pipeline maintains this efficiency while ensuring robust performance across diverse datasets, including clinical samples with pathological brain conditions that often challenge conventional processing pipelines [24].

Computational Cost Analysis in HPC Environments

The economic considerations of large-scale neuroimaging data processing extend beyond simple processing time metrics. A critical analysis of computational expenses reveals substantial differences between pipelines:

Table 2: Computational expense comparison in HPC environments

| Pipeline | CPU Allocation | Processing Time | Relative Computational Expense | Cost Efficiency Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DeepPrep [24] | Flexible (1-16 CPUs) | Stable across configurations | 5.8-22.1× lower than fMRIPrep | Dynamic resource allocation |

| fMRIPrep [24] | 1 CPU | ~6 hours | Baseline | N/A |

| fMRIPrep [24] | 16 CPUs | ~1 hour | Up to 22.1× higher than DeepPrep | Characteristic trade-off curve |

DeepPrep's stability in both processing time and expenses across different CPU allocations stems from its computational flexibility in dynamically allocating resources to match specific task requirements [24]. This represents a significant advantage for researchers working within constrained computational budgets, particularly when processing large-scale datasets.

Experimental Protocols for Scalable Neuroimaging

Protocol: Large-Scale Connectome Mapping Pipeline

This protocol outlines the methodology for mapping structural connectivity across large cohorts (n=1,800+ participants) using cloud-integrated HPC resources, based on validated approaches from published research [28].

Materials and Reagents

- High-quality diffusion MRI data

- T1-weighted structural images

- Population receptive field (pRF) mapping data

- Computational resources: Texas Advanced Computing Center (TACC) HPC clusters or equivalent cloud infrastructure

- Software platform: brainlife.io open-source platform

Procedure

- Data Acquisition and Transfer

- Acquire multi-shell diffusion MRI data with appropriate b-values (e.g., b=1000, 2000 s/mm²)

- Collect high-resolution T1-weighted anatomical images (1mm³ isotropic resolution recommended)

- Transfer data to HPC or cloud storage with integrity verification

Diffusion MRI Preprocessing

- Perform denoising using patch-based algorithms (e.g., MRTrix3 dwidenoise)

- Correct for eddy currents and subject motion using FSL eddy with outlier replacement

- Conduct B1 field inhomogeneity correction

Tractography Reconstruction

- Reconstruct fiber orientation distributions using constrained spherical deconvolution

- Generate whole-brain tractography with deterministic or probabilistic algorithms (e.g., 10 million streamlines)

- Apply spherical-deconvolution informed filtering of tractograms (SIFT) to reduce reconstruction bias

Visual Cortex Parcellation

- Map visual field representations onto cortical surface using population receptive field (pRF) modeling

- Subdivide visual areas according to visual field coordinates (upper/lower vertical meridian, horizontal meridian)

- Coregister pRF maps with diffusion data in common space

Connectivity Quantification

- Calculate connectivity density as number of axonal connections between visual areas divided by region volume

- Separate intra-occipital connections (within visual cortex) from long-range connections (afferent to visual areas)

- Normalize connectivity measures by region volume

Statistical Analysis

- Perform repeated-measures ANOVA to examine connectivity asymmetries

- Conduct post-hoc t-tests with multiple comparison correction (FDR, p<0.05)

- Implement lifespan analyses using linear mixed-effects models

Validation and Quality Control

- Verify pipeline performance by replicating known visual asymmetries (higher connectivity along horizontal vs. vertical meridians)

- Confirm expected hemispheric differences in connectivity patterns

- Implement automated quality control metrics for tractography reconstruction

Protocol: Reproducible Processing with BIDS App Bootstrap (BABS)

The BIDS App Bootstrap framework enables reproducible, large-scale image processing while maintaining complete provenance tracking [27].

Materials and Reagents

- BIDS-structured dataset

- BIDS App container (Docker or Singularity)

- HPC cluster with Slurm or SGE job scheduler

- DataLad installation (v0.15+)

Procedure

- Environment Setup

BABS Configuration

Workflow Initialization

Job Submission and Monitoring

Provenance Tracking and Reporting

Validation and Quality Control

- Verify complete audit trail for all processed participants

- Confirm checksum consistency for input and output files

- Validate BIDS derivatives compliance

- Ensure processing commands are fully recorded in DataLad history

Architecture and Workflow Visualization

Scalable Neuroimaging Architecture

The following diagram illustrates the integrated architecture of scalable neuroimaging pipelines across different computing environments:

Scalable Neuroimaging Architecture

Reproducible Processing Workflow

The workflow for reproducible large-scale processing using the BABS framework incorporates full provenance tracking:

Reproducible Processing Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit

Essential Platforms and Software Solutions

Table 3: Essential research reagent solutions for scalable neuroimaging

| Tool/Platform | Primary Function | Key Features | Computing Environment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neurodesk [26] [29] | Containerized analysis environment | Reproducible workflows, tool interoperability, BIDS compliance | Local, HPC, Cloud |

| DeepPrep [24] | Accelerated neuroimaging preprocessing | Deep learning integration, 10× acceleration, clinical robustness | GPU-equipped workstations, HPC |

| BABS [27] | Reproducible BIDS App processing | DataLad provenance, audit trail, HPC integration | Slurm, SGE HPC clusters |

| brainlife.io [28] | Open-source neuroscience platform | Automated pipelines, data management, visualization | Cloud-integrated HPC |

| DataLad [27] | Data version control | Git-annex integration, provenance tracking, distribution | Cross-platform |

| Flywheel [30] | Cloud data management | Data organization, metadata query, analysis pipelines | Cloud-agnostic |

Implementation Considerations

Computational Resource Allocation Effective utilization of cloud and HPC resources requires careful planning. Research teams should implement unique cost centers for labs and teams to promote responsible resource consumption [30]. The hidden costs of cloud computing, including long-running computational jobs, ingress/egress fees, and inefficient compute management, must be factored into project planning [30].

Data Organization and Management Structuring large multimodal data with comprehensive metadata enables programmatic access and intuitive exploration [30]. Data organization should be built into pipelines from the start rather than saved for later stages [30]. Distinguishing raw data from derived products with read-only permissions and avoiding data duplication supports effective access controls [30].

Environmental Sustainability The carbon footprint of neuroimaging data processing varies significantly across tools and approaches [31]. Measuring and comparing the environmental impact of different processing strategies, such as FSL, SPM, and fMRIPrep, enables researchers to make environmentally conscious decisions [31]. Climate-aware task schedulers and energy-efficient algorithms represent promising approaches for reducing the environmental impact of large-scale neuroimaging research [31].

Cloud and HPC platforms have become indispensable infrastructures for contemporary brain imaging research, enabling the processing and analysis of large-scale datasets that were previously computationally intractable. The integration of containerized software solutions, standardized data formats, and workflow management systems has enhanced both the reproducibility and accessibility of advanced neuroimaging analyses. Deep learning-accelerated pipelines like DeepPrep demonstrate order-of-magnitude improvements in processing efficiency while maintaining analytical accuracy [24]. Frameworks such as BABS provide critical provenance tracking capabilities that ensure the reproducibility of large-scale analyses [27].

Future developments in scalable neuroimaging will likely focus on several key areas. Federated learning approaches will enable collaborative model training across institutions without sharing raw data, addressing privacy and regulatory concerns [23]. The development of more energy-efficient algorithms and climate-aware scheduling systems will help mitigate the environmental impact of computation-intensive neuroimaging research [31]. Enhanced interoperability between platforms, standardized implementation of FAIR data principles, and continued innovation in deep learning applications will further advance the field. As these developments mature, researchers and drug development professionals will be increasingly equipped to translate large-scale brain imaging data into meaningful insights about brain structure, function, and disorders.

From Raw Data to Results: Workflow Tools and AI Methodologies

In modern brain imaging research, the choice of data processing workflow is a critical determinant of success. These workflows, or pipelines, are the structured sequences of computational steps that transform raw neuroimaging data into interpretable results. A fundamental dichotomy exists between fixed pipelines, which use a predetermined, standardized set of processing steps and parameters, and flexible pipelines, which allow for adaptive configuration, customization, and optimization of these steps. Fixed pipelines prioritize reproducibility, standardization, and ease of use, making them suitable for well-established analytical paths and large-scale data processing. In contrast, flexible pipelines emphasize optimization for specific research questions, adaptability to novel data types or experimental designs, and the ability to incorporate the latest algorithms, though they often require greater computational expertise and rigorous validation to ensure reliability.

The strategic selection between these approaches directly impacts the scalability, accuracy, and clinical applicability of research findings. For instance, the DeepPrep pipeline demonstrates the power of integrating deep learning modules to achieve a tenfold acceleration in processing time while maintaining robust performance across over 55,000 scans, including challenging clinical cases with brain distortions [24]. This document provides a structured framework, including application notes, experimental protocols, and decision aids, to guide researchers in selecting and implementing the optimal workflow strategy for their specific brain imaging projects.

Application Notes: Comparative Analysis of Pipeline Strategies

Performance Benchmarks and Clinical Applicability

Table 1: Quantitative Performance Comparison of Representative Pipelines

| Pipeline / Tool | Primary Strategy | Key Performance Metric | Reported Outcome | Clinical Robustness |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DeepPrep [24] | Flexible (AI-powered) | Processing Time | 10.1x faster than fMRIPrep (31.6 vs. 318.9 min) | 100% completion on distorted brains |

| fMRIPrep [24] | Fixed (Standardized) | Processing Time | Baseline (318.9 ± 43.2 min) | 69.8% completion on distorted brains |

| USLR [32] | Flexible (Longitudinal) | Analysis Power | Improved detection of group differences vs. cross-sectional | Enables subject-specific prediction |

| NeuroMark [33] | Hybrid (Spatial Priors + Data-Driven) | Predictive Accuracy | Outperforms predefined atlases | Captures individual variability for biomarkers |

The data in Table 1 reveals a clear trade-off. Flexible and hybrid pipelines, such as DeepPrep and NeuroMark, demonstrate superior performance in computational efficiency and the ability to capture individual subject variability, which is crucial for clinical translation and personalized medicine [24] [33]. The USLR framework highlights another strength of flexible approaches: by enforcing smooth, unbiased longitudinal registration, it achieves higher sensitivity in detecting subtle, clinically relevant changes like those in Alzheimer's disease, potentially reducing the sample sizes required in clinical trials [32].

However, the fixed pipeline approach, exemplified by tools like fMRIPrep, provides a critical foundation of standardization and reproducibility. The challenge of variability is starkly illustrated in functional connectomics, where a systematic evaluation of 768 data-processing pipelines revealed "vast and systematic variability" in their suitability, with the majority of pipelines failing at least one key criterion for reliability and sensitivity [34]. This underscores that an uninformed choice of a flexible pipeline can produce "misleading conclusions about neurobiology," whereas a set of optimal pipelines can consistently satisfy multiple criteria across different datasets [34].

A Framework for Functional Decomposition

Choosing a pipeline often involves selecting a strategy for functional decomposition—the method of parcellating the brain into functionally meaningful units for analysis. A useful framework classifies these decompositions along three key attributes [33]:

- Source: The origin of the decomposition (e.g., Anatomical, Functional, Multimodal).

- Mode: The nature of the brain units (e.g., Categorical/discrete regions vs. Dimensional/overlapping representations).

- Fit: The degree of data-driven adaptation (e.g., Predefined, Data-driven, Hybrid).

Table 2: Functional Decomposition Atlas Classification

| Atlas / Approach | Source | Mode | Fit | Typical Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AAL Atlas [33] | Anatomical | Categorical | Predefined | Standardized structural analysis |

| Yeo 17 Network [33] | Functional | Dimensional | Predefined | Resting-state network analysis |

| Fully Data-Driven ICA | Functional | Dimensional | Data-Driven | Exploratory analysis of a single study |

| NeuroMark Pipeline [33] | Functional | Dimensional | Hybrid (Spatially Constrained) | Individual differences, cross-study comparison |

Fixed pipelines typically employ predefined atlases (e.g., AAL, Yeo), which offer excellent interoperability and comparability across studies. In contrast, flexible workflows may leverage fully data-driven decompositions, which can better fit a specific dataset but struggle with cross-subject correspondence. Hybrid models, like the NeuroMark pipeline, represent a powerful compromise, using spatial priors derived from large datasets to ensure correspondence across subjects while allowing data-driven refinement to capture individual variability and dynamic spatial patterns [33]. This hybrid approach has been shown to boost sensitivity to individual differences while maintaining cross-subject generalizability [33].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Benchmarking Fixed vs. Flexible Preprocessing Pipelines

Objective: To quantitatively compare the processing time, computational resource utilization, and robustness of a fixed pipeline (e.g., fMRIPrep) against a flexible, AI-powered pipeline (e.g., DeepPrep) on a dataset that includes both healthy controls and pathological cases.

Materials:

- Imaging Data: A cohort of T1-weighted structural MRI and resting-state fMRI scans. The cohort should include at least 20 healthy control scans and 10 clinical scans from patients with conditions causing brain distortion (e.g., glioma, stroke) [24].

- Computing Environment: A high-performance computing (HPC) node or a local workstation equipped with CPUs and at least one GPU.

- Software: Docker or Singularity container platforms. The fixed pipeline (fMRIPrep) and the flexible pipeline (DeepPrep) should be installed as BIDS Apps [24].

Methodology:

- Data Standardization: Convert all raw DICOM files into the Brain Imaging Data Structure (BIDS) format. This can be automated using data management platforms like Flywheel, which provides built-in Gears for BIDS conversion [35].

- Pipeline Execution:

- Process the entire dataset (30 scans) through both fMRIPrep and DeepPrep.

- For resource analysis, run fMRIPrep by recruiting different CPU counts (e.g., 1, 2, 4, 8, 16) for a single participant and record the processing time and total CPU hours expended [24].

- Execute DeepPrep on the same participant in a GPU-enabled environment as recommended.

- Outcome Measures:

- Processing Time: Record the wall-clock time for each processed scan.

- Computational Cost: Calculate the total CPU hours and associated cloud computing costs (if applicable) for each pipeline.

- Pipeline Completion Ratio: For each pipeline, calculate the percentage of scans that completed preprocessing without fatal errors.

- Acceptable Ratio: Have a qualified analyst (or use an automated quality control tool) review the preprocessed outputs and visual reports for anatomical accuracy (e.g., correct tissue segmentation, surface reconstruction). Calculate the percentage of scans with acceptable quality [24].

Expected Outcomes: Anticipate results similar to the DeepPrep study, where the flexible pipeline showed a tenfold acceleration, lower computational expenses (5.8x to 22.1x lower), and superior completion (100% vs. 69.8%) and acceptable (58.5% vs. 30.2%) ratios on pathological brains [24].

Protocol 2: Evaluating the Impact of Pipeline Choice on Functional Connectomics

Objective: To assess how different data-processing pipelines for constructing functional brain networks affect the test-retest reliability and sensitivity to experimental effects of derived graph-theoretical metrics.

Materials:

- Imaging Data: A test-retest resting-state fMRI dataset, such as from the Human Connectome Project, where the same participant was scanned on multiple sessions [34].

- Pipelines: A subset of the 768 possible pipeline combinations generated by varying key steps [34]:

- Global Signal Regression (GSR): With vs. Without.

- Brain Parcellation (Node Definition): e.g., Anatomical (AAL), functional (Yeo), multimodal (Brainnetome).

- Number of Nodes: ~100, 200, or 300-400.

- Edge Definition: Pearson correlation vs. Mutual Information.

- Edge Filtering: Density-based (e.g., retain 5% of edges) vs. Weight-based (e.g., minimum weight 0.3) vs. Data-driven (Efficiency Cost Optimization).

- Network Type: Binary vs. Weighted.

Methodology:

- Network Construction: For a single subject's test-retest data, run a selected array of pipelines (e.g., 10-20 contrasting combinations) to reconstruct functional brain networks for each session.

- Topological Analysis: Calculate common network metrics (e.g., modularity, global efficiency) from each constructed network.

- Evaluation:

- Test-Retest Reliability: Calculate the intra-class correlation (ICC) of each network metric between the two sessions for each pipeline.

- Portrait Divergence (PDiv): Use this information-theoretic measure to compute the dissimilarity between the network topologies of the two sessions. A lower PDiv indicates higher reliability [34].

- Criterion Satisfaction: Classify each pipeline based on its ability to minimize motion confounds and spurious test-retest discrepancies while remaining sensitive to inter-subject differences.

Expected Outcomes: This protocol will likely reveal that a majority of pipeline combinations fail to meet all reliability and sensitivity criteria. The goal is to identify a subset of "optimal" pipelines that consistently produce reliable and sensitive network topologies, as demonstrated in the systematic evaluation by [34].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools for Brain Imaging Workflow Development

| Tool / Solution | Function | Relevance to Pipeline Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| BIDS (Brain Imaging Data Structure) [35] | A framework for organizing and describing neuroimaging datasets. | Foundational standard for both fixed and flexible pipelines, enabling interoperability and automated data ingestion. |

| Deep Learning Modules (e.g., FastSurferCNN, SUGAR) [24] | Pre-trained neural networks for specific tasks (segmentation, surface registration). | Core components of flexible, accelerated pipelines like DeepPrep, replacing conventional algorithms. |

| Containerization (Docker/Singularity) [24] | Packages software and all dependencies into a portable, reproducible unit. | Critical for deploying both fixed and flexible pipelines consistently across different computing environments. |

| Workflow Manager (Nextflow) [24] | Manages complex computational workflows, enabling scalability and portability. | Key for scalable execution of flexible pipelines in HPC and cloud environments, dynamic resource allocation. |

| Spatial Priors (e.g., NeuroMark Templates) [33] | Data-derived templates used to guide and regularize subject-level decomposition. | Enables hybrid analysis strategies, balancing individual specificity with cross-subject correspondence. |

| Simulation-Based Inference (SBI) Toolkits (e.g., VBI) [36] | Enables Bayesian parameter estimation for complex whole-brain models where traditional inference fails. | A flexible approach for model inversion, quantifying uncertainty in parameters for biophysically interpretable inference. |

Workflow Decision Diagrams

Strategic Pipeline Selection

Implementing a Flexible Hybrid Analysis

The analysis of brain imaging data presents a significant challenge in terms of complexity, reproducibility, and scalability. Fixed neuroimaging pipelines address these challenges by providing standardized, automated workflows that ensure consistent processing across datasets and research groups. Within the broader context of brain imaging data analysis workflows research, these pipelines transform raw, complex magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) data into reliable, analyzable metrics, thereby accelerating scientific discovery and facilitating cross-study comparisons. This article examines three specialized pipelines—CIVET, PANDA, and DPARSF—that have been developed for distinct analysis types: cortical morphology, white matter integrity, and resting-state brain function, respectively. Each represents a tailored solution to specific analytical challenges while embodying the core principles of automation, standardization, and reproducibility that are crucial for advancing neuroimaging science. By integrating these pipelines into their research, scientists and drug development professionals can enhance methodological rigor, reduce processing errors, and focus intellectual resources on scientific interpretation rather than technical implementation.

Table 1: Overview of Specialized Neuroimaging Pipelines

| Pipeline | Primary Analysis Type | Core Function | Input Data | Key Outputs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CIVET | Cortical Morphology | Automated cortical surface extraction | T1-weighted MRI | Cortical thickness, surface models |

| PANDA | White Matter Integrity | Diffusion image processing | Diffusion MRI | Fractional Anisotropy (FA), Mean Diffusivity (MD), structural networks |

| DPARSF | Resting-State fMRI | Resting-state fMRI preprocessing & analysis | Resting-state fMRI | Functional connectivity, ALFF, ReHo |

Pipeline-Specific Methodologies and Protocols

CIVET: Cortical Morphometry Pipeline

The CIVET pipeline specializes in automated extraction of cortical surfaces and precise evaluation of cortical thickness from structural MRI data. Originally developed for human neuroimaging, it has been successfully extended for processing macaque brains, demonstrating its adaptability across species [37]. The processing is performed using the NIMH Macaque Template (NMT) as the reference template, with anatomical parcellation of the surface following the D99 and CHARM atlases [37]. This pipeline has been robustly applied to process anatomical scans of 31 macaques used to generate the NMT and an additional 95 macaques from the PRIME-DE initiative, confirming its scalability to substantial datasets [37]. The open usage of CIVET-macaque promotes collaborative efforts in data collection, processing, sharing, and automated analyses, advancing the non-human primate brain imaging field through methodological standardization.

CIVET Processing Workflow: From raw T1-weighted MRI to cortical thickness statistics.

PANDA: Automated Diffusion MRI Analysis

PANDA (Pipeline for Analyzing braiN Diffusion imAges) is a MATLAB toolbox designed for fully automated processing of brain diffusion images, addressing a critical gap in the streamlined analysis of white matter microstructure [38] [39]. The pipeline integrates processing modules from established packages including FMRIB Software Library (FSL), Pipeline System for Octave and Matlab (PSOM), Diffusion Toolkit, and MRIcron, creating a cohesive workflow that transforms raw diffusion MRI datasets into analyzable metrics [38] [39]. PANDA accepts any number of raw dMRI datasets from different subjects in either DICOM or NIfTI format and automatically performs a comprehensive series of processing steps to generate diffusion metrics—including fractional anisotropy (FA), mean diffusivity (MD), axial diffusivity (AD), and radial diffusivity (RD)—that are ready for statistical analysis at multiple levels [38]. A distinctive advantage of PANDA is its capacity for parallel processing of different subjects using multiple cores either in a single computer or in a distributed computing environment, substantially reducing computational time for large-scale studies [38] [39].

Table 2: PANDA Processing Modules and Functions

| Processing Stage | Specific Operations | Software Tools Utilized |

|---|---|---|

| Preprocessing | DICOM to NIfTI conversion, brain mask estimation, image cropping, eddy-current correction, tensor calculation | MRIcron (dcm2nii), FSL (bet, fslroi, flirt, dtifit) |

| Diffusion Metric Production | Normalization to standard template, voxel-level, atlas-level, and TBSS-level analysis ready outputs | FSL (fnirt) |

| Network Construction | Whole-brain structural connectivity mapping, deterministic and probabilistic tractography | Diffusion Toolkit, FSL |

The PANDA processing protocol follows three methodical stages. First, in preprocessing, DICOM files undergo conversion to NIfTI format using the dcm2nii tool, followed by brain mask estimation via FSL's bet command [38] [39]. The images are then cropped to remove non-brain spaces, reducing memory requirements for subsequent steps. Eddy-current-induced distortion and simple head motion are corrected by registering diffusion-weighted images to the b0 image using an affine transformation through FSL's flirt command, with appropriate rotation of gradient directions [38]. For studies involving multiple acquisitions, the corrected images are averaged before voxel-wise calculation of the tensor matrix and diffusion metrics using FSL's dtifit command. Second, for producing analysis-ready diffusion metrics, PANDA performs spatial normalization by non-linearly registering individual FA images to a standard FA template in MNI space using FSL's fnirt command, establishing the location correspondence necessary for cross-subject comparisons [38] [39]. Finally, the pipeline enables construction of anatomical brain networks through either deterministic or probabilistic tractography techniques, automatically generating structural connectomes for network-based analyses [38].

PANDA Workflow: Comprehensive processing of diffusion MRI from raw data to multiple analysis endpoints.

DPARSF: Resting-State fMRI Data Processing

DPARSF (Data Processing Assistant for Resting-State fMRI) addresses the critical need for user-friendly pipeline analysis of resting-state fMRI data, providing an accessible solution based on Statistical Parametric Mapping (SPM) and the Resting-State fMRI Data Analysis Toolkit (REST) [40] [41]. This MATLAB toolbox enables researchers to efficiently preprocess resting-state fMRI data and compute key metrics of brain function, including functional connectivity (FC), regional homogeneity (ReHo), amplitude of low-frequency fluctuation (ALFF), and fractional ALFF (fALFF) [40] [41]. The pipeline accepts DICOM files and, through minimal button-clicking parameter settings, automatically generates fully preprocessed data and analytical results, substantially simplifying the often complex workflow associated with resting-state fMRI analysis. DPARSF also creates quality control reports for excluding subjects with excessive head motion and generates visualization pictures for checking normalization effects, features that are essential for maintaining data quality in both single-site studies and large-scale multi-center investigations [40].

The DPARSF protocol encompasses comprehensive preprocessing and analytical stages. After converting DICOM files to NIfTI format using the dcm2nii tool, the pipeline typically removes the first 10 time points to allow for signal equilibrium [41]. Slice timing correction addresses acquisition time differences between slices, followed by head motion correction to adjust the time series of images so the brain maintains consistent positioning across all acquisitions [41]. DPARSF creates a report of head motion parameters to facilitate the exclusion of subjects with excessive movement. Spatial normalization then transforms individual brains into standardized Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) space using either an EPI template or unified segmentation of T1 images, with the latter approach improving normalization accuracy [41]. The pipeline generates visualization pictures to enable researchers to check normalization quality for each subject. Subsequent smoothing with a Gaussian kernel suppresses noise and residual anatomical differences, followed by linear trend removal to eliminate systematic signal drifts [41]. For frequency-based analyses, bandpass filtering (typically 0.01-0.08 Hz) isolates low-frequency fluctuations of physiological significance while reducing high-frequency physiological noise [41]. The pipeline then computes key resting-state metrics: functional connectivity assesses temporal correlations between brain regions; regional homogeneity (ReHo) measures local synchronization using Kendall's coefficient of concordance; and ALFF/fALFF quantify the amplitude of spontaneous low-frequency oscillations [40] [41].

DPARSF Workflow: Automated processing of resting-state fMRI with integrated quality control.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Resources

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Compatibility/Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|

| FSL (FMRIB Software Library) | Software Library | Comprehensive MRI data analysis | Used by PANDA for diffusion processing |

| SPM (Statistical Parametric Mapping) | Software Package | Statistical analysis of brain imaging data | Core dependency for DPARSF |

| REST (Resting-State fMRI Data Analysis Toolkit) | Software Toolkit | Resting-state fMRI analysis | Integrated with DPARSF |

| NMT (NIMH Macaque Template) | Reference Template | Standard space for non-human primate data | Used by CIVET for macaque processing |

| D99 & CHARM Atlases | Parcellation Atlas | Anatomical labeling of brain regions | Surface parcellation in CIVET |

| MRIcron (dcm2nii) | Conversion Tool | DICOM to NIfTI format conversion | Used by both PANDA and DPARSF |

Comparative Analysis and Implementation Considerations

When selecting and implementing these fixed workflows, researchers must consider several practical aspects. Computational requirements represent a significant factor, with PANDA's support for parallel processing across multiple cores or computing clusters offering substantial efficiency gains for large diffusion MRI datasets [38] [39]. DPARSF similarly offers parallel computing capabilities when used with MATLAB's Parallel Computing Toolbox, dramatically reducing processing time for sizeable resting-state fMRI studies [40]. Quality control integration varies across pipelines, with DPARSF providing automated head motion reports and normalization quality visualizations [40] [41], while more recent frameworks like RABIES for rodent fMRI generate comprehensive quality control reports for registration operations and data diagnostics [42]. These quality assurance features are crucial for maintaining analytical rigor, particularly in large-scale studies or when combining datasets from multiple sites.

Flexibility within standardized workflows is another key consideration. While these pipelines offer fixed processing pathways, several provide configurable parameters—PANDA includes a friendly graphical user interface for adjusting input/output settings and processing parameters [38] [39], and DPARSF allows users to select different processing templates and analytical options [40]. This balance between standardization and configurability enables researchers to maintain methodological consistency while accommodating study-specific requirements. Implementation success also depends on proper data organization, with emerging standards like the Brain Imaging Data Structure (BIDS) being supported by modern pipelines such as RABIES to ensure compatibility and reproducibility [42]. For researchers working across multiple species, the adaptability of these pipelines is demonstrated by CIVET's extension to macaque data [37] and specialized implementations like RABIES for rodent imaging [42], highlighting the translatability of fixed workflow principles across model systems.

Fixed neuroimaging pipelines like CIVET, PANDA, and DPARSF represent transformative tools that standardize complex analytical processes across diverse MRI modalities. By providing automated, standardized workflows for cortical morphometry, white matter integrity, and resting-state brain function, these pipelines enhance methodological reproducibility, reduce processing errors, and accelerate the pace of discovery in brain imaging research. Their ongoing development and adaptation to new species, imaging modalities, and computational environments underscore the dynamic nature of neuroinformatics and its critical role in advancing neuroscience. For researchers and drug development professionals, mastering these fixed workflows offers the opportunity to generate more reliable, comparable, and scalable results, ultimately strengthening the foundation upon which our understanding of brain structure and function is built.

The complexity of modern brain imaging data necessitates robust, scalable, and reproducible analysis workflows. Flexible workflow environments address this need by enabling researchers to construct, validate, and execute customized processing protocols by linking together disparate neuroimaging software tools. These environments are crucial within a broader brain imaging data analysis research context as they facilitate methodologically sound, efficient, and transparent analyses, directly accelerating progress in neuroscience and drug development. This document provides detailed application notes and experimental protocols for three leading flexible workflow environments: LONI Pipeline, Nipype, and JIST. By summarizing their capabilities, providing direct comparative data, and outlining step-by-step methodologies, this guide aims to empower researchers and scientists to select and implement the optimal workflow solution for their specific research objectives.

Workflow Environment Comparison

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Flexible Workflow Environments

| Feature | LONI Pipeline | Nipype | JIST (Java Image Science Toolkit) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Interface | Graphical User Interface (GUI) [43] | Python-based scripting [44] | Graphical User Interface (GUI) [43] |

| Tool Integration | Modules from AFNI, SPM, FSL, FreeSurfer, Diffusion Toolkit [43] | Interfaces for ANTs, SPM, FSL, FreeSurfer, AFNI, MNE, Camino, and many others [44] [45] | Modules from predefined libraries; allows linking of in-house modules [43] |

| Workflow Type | Flexible [43] | Flexible [43] | Flexible [43] |

| Parallel Computing | Supports multi-core systems, distributed clusters (SGE, PBS, LSF), grid/cloud computing [43] [46] | Parallel processing on multiple cores/machines [45] | Supports parallel computing on a single computer or across a distributed cluster [43] |

| Key Strength | User-friendly GUI; strong provenance tracking; decentralized grid computing [43] [46] | Unprecedented software interoperability in a single workflow; high flexibility and reproducibility [45] | Intuitive GUI for workflow construction; surface reconstruction workflows [43] |

Detailed Environment Specifications

LONI Pipeline

LONI Pipeline is a distributed, grid-enabled environment designed for constructing complex scientific analyses. Its architecture separates the client interface from backend computational servers, allowing users to leverage remote computing resources and extensive tool libraries [46] [47]. A core strength is its data provenance model, which automatically records the entire history of data, workflows, and executions, ensuring reproducibility and facilitating the validation of scientific findings [46]. The environment includes a validation and quality control system that checks for data type consistency, parameter matches, and protocol correctness before workflow execution, with options for visual inspection of interim results [43].

Nipype