Balancing Exploration and Exploitation in Neural Population Algorithms: A Guide for Biomedical Research and Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of strategies for balancing exploration and exploitation within neural population algorithms, with a specific focus on applications in drug discovery and biomedical research.

Balancing Exploration and Exploitation in Neural Population Algorithms: A Guide for Biomedical Research and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of strategies for balancing exploration and exploitation within neural population algorithms, with a specific focus on applications in drug discovery and biomedical research. It begins by establishing the foundational principles of this core trade-off, detailing its critical role in evolutionary and population-based search methods. The content then progresses to examine cutting-edge methodological frameworks, including Population-Based Guiding (PBG) and other bio-inspired optimization techniques. A practical troubleshooting section addresses common challenges such as premature convergence and deceptive reward landscapes, offering targeted optimization strategies. Finally, the article presents a rigorous validation and comparative analysis, benchmarking algorithmic performance against established standards and demonstrating their efficacy through real-world use cases in de novo molecular design and predictive healthcare models. This resource is tailored for researchers and professionals seeking to leverage these advanced algorithms to accelerate innovation in their fields.

The Core Dilemma: Understanding Exploration-Exploitation in Population-Based Search

Core Concepts FAQ

What is the exploration-exploitation dilemma in the context of optimization algorithms? The exploration-exploitation dilemma describes the fundamental challenge of balancing two opposing strategies: exploitation, which involves selecting the best-known option based on current knowledge to maximize immediate reward, and exploration, which involves trying new or less-familiar options to gather information, with the goal of discovering options that may yield higher rewards in the future [1]. In computational fields like reinforcement learning and meta-heuristic optimization, this trade-off is crucial for maximizing long-term cumulative benefits [1] [2].

How does this trade-off manifest in neural population dynamics and drug discovery? In brain-inspired meta-heuristic algorithms like the Neural Population Dynamics Optimization Algorithm (NPDOA), this dilemma is managed through specific neural strategies. The attractor trending strategy drives populations towards optimal decisions (exploitation), while the coupling disturbance strategy deviates populations from these attractors to improve exploration [3]. Similarly, in de novo drug design, the dilemma appears as a conflict between generating the single highest-scoring molecule (pure exploitation) and generating a diverse batch of high-scoring molecules (combining exploration and exploitation) to mitigate the risk of collective failure due to unmodeled properties [4].

What are the main types of exploration strategies? Research, particularly from behavioral and neuroscience studies, identifies two primary strategies that humans and algorithms use [5] [6]:

- Directed Exploration (Information-Seeking): A deterministic bias towards options with the highest uncertainty or information gain potential. It is computationally more intensive.

- Random Exploration (Behavioral Variability): The introduction of stochasticity or noise into the decision-making process. This is computationally simpler and can be effective for initial learning.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Issue 1: Algorithm Prematurely Converges to a Local Optimum

- Problem: Your optimization algorithm gets stuck in a local optimum, failing to find a better, global solution. This indicates insufficient exploration.

- Solution A: Increase directed exploration by implementing an uncertainty bonus. Modify the value function

Q(a)of an option 'a' from simply its expected rewardr(a)toQ(a) = r(a) + IB(a), whereIB(a)is an information bonus proportional to the uncertainty about 'a' [5]. The Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) algorithm is a classic example of this strategy [6]. - Solution B: Enhance random exploration through adaptive methods. Instead of a fixed exploration rate, use methods like Thompson Sampling, which scales exploration with the agent's uncertainty [5] [6]. For population-based algorithms, guide mutations towards less-visited regions of the search space, as seen in the PBG-0 variant [7].

Issue 2: Excessive Exploration Leading to Low Reward and Slow Convergence

- Problem: The algorithm spends too much time exploring suboptimal options, resulting in slow convergence and poor cumulative reward. This indicates a failure to effectively exploit gathered knowledge.

- Solution A: Implement a scheduled reduction in random exploration. For example, use an epsilon-decay strategy where the probability of taking a random action

εstarts high and decays over time, allowing a gradual transition from exploration to exploitation [8]. - Solution B: Strengthen exploitative mechanisms. In neural population algorithms, reinforce the attractor trending strategy that drives populations toward the current best-known solutions [3]. In evolutionary NAS, employ a greedy selection operator that prioritizes the best-performing parent architectures for reproduction [7].

Issue 3: Lack of Diverse Solutions in De Novo Molecular Generation

- Problem: Your goal-directed generative model produces a batch of nearly identical, high-scoring molecules, lacking the structural diversity required for a successful drug discovery campaign.

- Solution A: Integrate an explicit diversity objective. Modify the scoring function to penalize similarity between generated molecules. Frameworks like MAP-Elites or Memory-RL can be used to sort molecules into niches or memory units, preventing over-crowding in any single region of chemical space [4].

- Solution B: Adopt a probabilistic batch selection framework. Instead of selecting only the top-n scored molecules, select a batch that maximizes the expected success rate while considering that failure risks might be correlated for highly similar molecules. This formally reconciles the optimization objective with the need for diversity [4].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: Isolating Directed vs. Random Exploration in Behavioral Tasks

This protocol, adapted from experimental psychology, helps dissect which exploration strategy an algorithm or human subject is employing [6].

- Task Design: Implement a two-armed bandit task where one arm has a stochastic reward (unknown mean) and the other has a fixed, known reward (e.g., 0).

- Manipulation: Systematically vary the number of trials (time horizon) or the initial uncertainty about the stochastic arm.

- Measurement: Record the choice probability as a function of the estimated value difference between the two arms.

- Analysis:

- Fit a sigmoidal function to the choice probability data.

- A change in the response bias (intercept) with increased uncertainty is a signature of a directed exploration strategy (e.g., UCB) [6].

- A change in the response slope with increased uncertainty is a signature of an uncertainty-driven random exploration strategy (e.g., Thompson Sampling) [6].

Protocol 2: Benchmarking Exploration-Exploitation Balance in Meta-heuristic Algorithms

A standardized method to evaluate the performance of algorithms like NPDOA on benchmark problems [3].

- Selection of Benchmarks: Use a suite of standard single-objective optimization problems, including non-convex and nonlinear functions (e.g., cantilever beam design, pressure vessel design) [3].

- Algorithm Configuration: Implement the algorithm with its core strategies:

- Attractor Trending: Drives population toward attractors representing good solutions.

- Coupling Disturbance: Disrupts convergence via interactions between populations.

- Information Projection: Regulates the influence of the above two strategies [3].

- Evaluation Metrics:

- Final Solution Quality: Best objective value found.

- Convergence Speed: Number of iterations or function evaluations to reach a solution within a threshold of the global optimum.

- Robustness: Performance consistency across different benchmark problems.

- Comparison: Compare against established meta-heuristic algorithms like Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), Genetic Algorithm (GA), and Whale Optimization Algorithm (WOA) [3].

Table 1: Key Metrics for Benchmarking Algorithm Performance

| Metric | Description | Indicates Effective... |

|---|---|---|

| Best Objective Value | The highest (or lowest) value of the objective function found. | Exploitation |

| Convergence Iterations | The number of cycles required to find a near-optimal solution. | Overall Balance |

| Performance across Problems | Consistency of results on different benchmark functions. | Robustness |

Protocol 3: Evaluating Molecular Diversity in Goal-Directed Generation

A methodology to quantify whether a generative model produces diverse, high-quality molecules [4].

- Model Training: Train your goal-directed generation model (e.g., a reinforcement learning agent on a SMILES generator) to maximize a scoring function

S(m). - Batch Generation: Use the trained model to generate a large batch of candidate molecules (e.g., 10,000).

- Diversity Quantification:

- Calculate the pairwise Tanimoto similarity based on molecular fingerprints for all molecules in the batch.

- Compute the average similarity and the number of unique molecular scaffolds.

- Analysis: Compare the diversity metrics of your model against baselines. A successful model should achieve a high average score while maintaining low average similarity and a high number of unique scaffolds.

Table 2: Reagents and Computational Tools for Exploration-Exploit Research

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Multi-Armed Bandit (MAB) Task | A classic experimental paradigm to test exploration-exploitation decisions in a controlled setting [6]. |

| Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) | An algorithm that adds an uncertainty bonus to expected rewards to guide directed exploration [5] [6]. |

| Thompson Sampling | A Bayesian algorithm that selects actions by sampling from posterior distributions, enabling uncertainty-driven random exploration [5] [6]. |

| PlatEMO | A software platform for conducting experimental comparisons of multi-objective and, by extension, single-objective optimization algorithms [3]. |

| ChEMBL/PubChem | Public databases containing millions of molecules and bioactivity data, used as training data for drug discovery machine learning models [9]. |

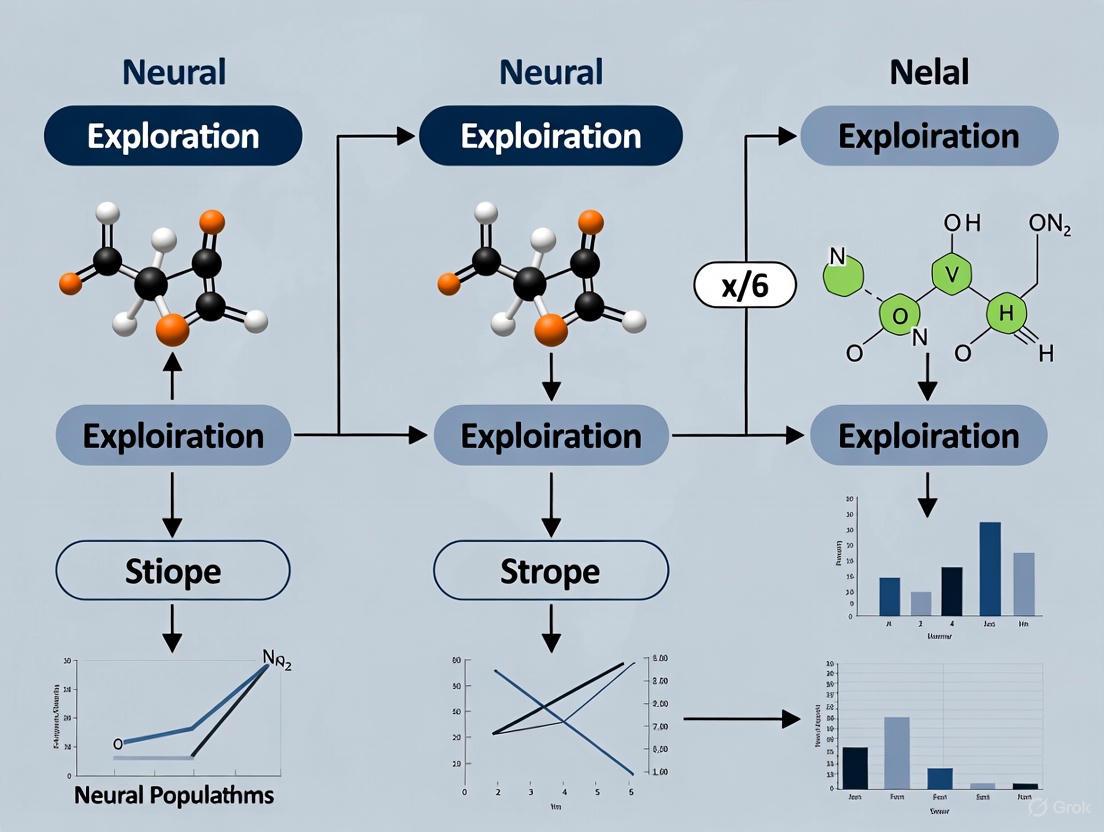

Conceptual Diagrams

Directed vs. Random Exploration Pathways

Neural Population Dynamics Optimization (NPDOA) Workflow

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What are the core strategies for balancing exploration and exploitation in algorithms? Researchers have identified two primary strategies. Directed exploration involves an explicit, calculated bias towards options that provide more information, often by adding an "information bonus" to the value of less-known options. In contrast, Random exploration introduces stochasticity into the decision-making process, such as adding random noise to value estimates, which can lead to choosing new options by chance [5]. Algorithms like Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) epitomize directed exploration, while methods like epsilon-greedy and Thompson Sampling are common implementations of random exploration [10].

Q2: Why is my neural network model failing to learn or converging poorly? Poor convergence often stems from foundational issues rather than the core algorithm itself. Common reasons include:

- Buggy Code: Neural networks can fail silently. Common bugs include incorrect tensor shapes, unused variables due to copy-paste errors, or faulty gradient calculations [11] [12].

- Unscaled Data: The scale of input data can drastically impact training. Data should typically be normalized to have a zero mean and unit variance or scaled to a small interval like [-0.5, 0.5] [11] [12].

- Inappropriate Architecture: Starting with an overly complex model for a new problem is a frequent pitfall. It is better to begin with a simple architecture (e.g., a fully-connected network with one hidden layer) and incrementally add complexity [11] [12].

Q3: How does the exploration-exploitation trade-off manifest in drug development? The high failure rate of clinical drug development—approximately 90%—can be viewed through this lens. A significant reason for failure is an over-emphasis on exploiting a drug's potency and specificity (Structure-Activity Relationship, or SAR) while under-exploring its tissue exposure and selectivity (Structure-Tissue Exposure/Selectivity Relationship, or STR) [13]. This imbalance can lead to selecting drug candidates that have high potency in lab assays but poor efficacy or unmanageable toxicity in human tissues, as their behavior in the complex biological "space" of the human body remains underexplored [13].

Q4: What is a practical first step to debug a underperforming neural network model? A highly recommended heuristic is to overfit a single batch of data. If your model cannot drive the training loss on a very small dataset (e.g., a single batch) arbitrarily close to zero, it indicates a fundamental bug or configuration issue rather than a generalizability problem. Failure to overfit a single batch can reveal issues like incorrect loss functions, exploding gradients, or data preprocessing errors [11].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Troubleshooting Poor Convergence in Neural Network Training

This guide helps diagnose and fix issues when your model's training loss does not decrease.

| Observed Symptom | Potential Causes | Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Training loss does not decrease at all; model predicts a constant. | • Implementation bugs (e.g., unused layers, incorrect loss) [12]• Data not normalized [11]• Extremely high learning rate | 1. Verify code with unit tests [12].2. Normalize input data (e.g., scale to [0,1]) [11].3. Overfit a single batch to test model capacity [11]. |

Training loss explodes to NaN. |

• Numerical instability [11]• High learning rate | 1. Use built-in framework functions (e.g., from Keras) to avoid manual math [11].2. Drastically reduce the learning rate. |

| Initial steep decrease in loss, then immediate plateau. | • Model fitting a constant to the target [12]• Learning rate too low after initial progress | 1. Ensure your model architecture is sufficiently complex for the problem [12].2. Increase the learning rate or use a learning rate scheduler. |

| Error oscillates wildly during training. | • Learning rate too high• Noisy or incorrectly shuffled labels [11] | 1. Lower the learning rate.2. Inspect your data pipeline for correctness in labels and augmentation [11]. |

Guide 2: Troubleshooting Exploration-Exploitation Imbalances in Algorithm Design

This guide addresses issues where an algorithm gets stuck in sub-optimal solutions or fails to discover new knowledge.

| Observed Symptom | Potential Causes | Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Algorithm converges too quickly to a sub-optimal solution (Excessive Exploitation). | • Epsilon-greedy with too small an ε [10]• Lack of an explicit information bonus in value estimation [5] |

1. Increase the exploration parameter (ε) or implement a decay schedule [10].2. Switch to a directed exploration algorithm like Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) [10] [5]. |

| Algorithm behaves too randomly and fails to consolidate learning (Excessive Exploration). | • Epsilon-greedy with too large an ε [10]• Decision noise not annealing over time [10] [5] |

1. Decrease the exploration parameter (ε) [10].2. Implement annealing to reduce random exploration over time [5]. |

| Poor performance in non-stationary environments (where the best option changes). | • Algorithm lacks mechanism to track changing reward distributions.• Exploration has been shut off too aggressively. | 1. Use algorithms designed for non-stationary environments or reset uncertainty estimates.2. Implement Thompson Sampling, which naturally scales exploration with uncertainty [10]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Benchmarking Exploration-Exploitation Algorithms

Objective: To compare the performance of different exploration-exploitation algorithms (e.g., Epsilon-Greedy, UCB, Thompson Sampling) in a controlled multi-armed bandit setting.

Methodology:

- Environment Setup: Simulate a multi-armed bandit with a fixed number of arms (e.g., 10). Each arm has a true, latent reward probability from a defined distribution.

- Algorithm Implementation:

- Epsilon-Greedy: With a fixed probability

ε(e.g., 0.1), explore a random arm; otherwise, exploit the arm with the highest current average reward [10]. - Upper Confidence Bound (UCB): Select the arm

athat maximizesQ(a) + c * √(ln t / N(a)), whereQ(a)is the average reward,N(a)is the number of times armahas been selected,tis the total number of plays, andcis a confidence parameter [10] [5]. - Thompson Sampling: Model the reward distribution of each arm (e.g., as a Beta distribution). For each play, sample a reward value from each arm's distribution and select the arm with the highest sampled value. Update the distribution based on the actual reward received [10].

- Epsilon-Greedy: With a fixed probability

- Evaluation: Run each algorithm for a fixed number of trials (e.g., 10,000). Track the cumulative regret (the difference between the reward of the optimal arm and the chosen arm) and the percentage of times the optimal arm is selected.

Protocol 2: Systematically Debugging a Deep Neural Network

Objective: To identify and resolve issues preventing a deep neural network from learning effectively.

Methodology:

- Start Simple:

- Use a simple architecture (e.g., one hidden layer) and sensible defaults (ReLU activation, no regularization) [11].

- Simplify the problem by working with a small, manageable dataset (~10,000 examples) and fixed input sizes [11].

- Normalize your inputs by subtracting the mean and dividing by the standard deviation [11] [12].

- Implement and Debug:

- Get the model to run: Use a debugger to step through model creation, checking for tensor shape mismatches and data types [11].

- Overfit a single batch: The most critical step. Take a single, small batch (e.g., 64 samples) and iterate until the loss approaches zero. Failure here indicates a serious bug [11].

- Evaluate and Compare:

- Compare your model's performance on a benchmark dataset to a known result or a simple baseline (e.g., linear regression) to ensure it is learning meaningfully [11].

Algorithm Comparison & Research Toolkit

Quantitative Comparison of Exploration Algorithms

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of three common exploration-exploitation algorithms, helping you select the right one for your context.

| Algorithm | Exploration Type | Key Mechanism | Typical Performance | Common Pitfalls |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Epsilon-Greedy [10] | Random | With probability ε, chooses a random action; otherwise, chooses the best-known action. |

Simple and often effective, but can be inefficient in complex reward landscapes. | Inefficient exploration; suboptimal actions are explored equally, regardless of potential. |

| Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) [10] [5] | Directed | Chooses the action with the highest upper confidence bound, balancing estimated value and uncertainty. | Systematically efficient; often achieves lower regret than epsilon-greedy. | Can be computationally intensive with large action spaces; requires parameter tuning. |

| Thompson Sampling [10] [5] | Random (Probability Matching) | Samples from the posterior distribution of reward beliefs and chooses the action with the highest sampled value. | Tends to exhibit superior performance in practice, especially in non-stationary environments. | Complex to implement due to requirement of maintaining and updating probability distributions. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Solutions

This table details essential conceptual "reagents" for research in this field.

| Item / Concept | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Multi-Armed Bandit Task | A classic experimental framework used to study the explore-exploit dilemma, where an agent must choose between multiple options (bandits) with unknown reward probabilities [5]. |

| Information Bonus | A value added to the expected reward of an action to promote directed exploration. It is often proportional to the uncertainty about that action [5]. |

| Softmax Function | A function that converts a set of values into a probability distribution, controlling the level of random exploration via a temperature parameter. Higher temperature leads to more random choices [5]. |

| Structure-Activity Relationship (SAR) | A drug optimization process that focuses on exploiting and improving a compound's potency and specificity for its intended target [13]. |

| Structure-Tissue Exposure/Selectivity Relationship (STR) | A drug optimization process that focuses on exploring and understanding a compound's behavior in the complex biological space of tissues and organs, crucial for predicting efficacy and toxicity [13]. |

Conceptual Diagrams

Exploration Strategies in Decision-Making

Neural Network Troubleshooting Workflow

STAR Framework in Drug Development

In computational optimization for neural population algorithms and drug development, researchers face the fundamental challenge of balancing exploration (searching for new, potentially better solutions) and exploitation (refining known good solutions). Two key theoretical frameworks address this dilemma: Multi-Armed Bandit (MAB) problems, which provide formal models for sequential decision-making under uncertainty, and metaheuristic algorithms, which offer high-level strategies for navigating complex search spaces [5] [14]. Recent advances in brain-inspired optimization have introduced novel approaches like the Neural Population Dynamics Optimization Algorithm (NPDOA), which mimics decision-making processes in neural circuits [3]. This technical support center provides practical guidance for implementing these frameworks in research settings, with specific troubleshooting advice for common experimental challenges.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: How can I prevent my optimization algorithm from converging prematurely to suboptimal solutions?

Premature convergence typically indicates insufficient exploration. Implement the following solutions:

- In MAB setups: Increase exploration using algorithms like ε-Greedy, Upper Confidence Bound (UCB), or Thompson Sampling [15]. For ε-Greedy, start with ε = 0.1 and decay it slowly over iterations.

- In metaheuristics: Use NPDOA's coupling disturbance strategy, which deliberately disrupts convergence trends to push the search toward unexplored regions [3].

- General approach: Combine both directed exploration (explicit information seeking) and random exploration (behavioral variability) strategies [5].

FAQ 2: What metrics should I use to quantitatively evaluate the exploration-exploitation balance in my experiments?

Track these key metrics throughout optimization runs:

Table: Key Evaluation Metrics for Exploration-Exploitation Balance

| Metric | Description | Target Range | Measurement Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average Reward Trend | Slope of cumulative rewards over time | Increasing positive slope | Linear regression on reward sequence [15] |

| Population Diversity | Variance in solution characteristics | Maintain >15% of initial variance | Genotypic/phenotypic diversity measures [7] |

| Optimal Action Rate | Percentage of trials selecting best-known option | Gradually increasing to >80% | Action selection frequency analysis [16] |

| Regret | Difference between optimal and actual rewards | Decreasing over time | Cumulative regret calculation [17] |

FAQ 3: How do I adapt MAB algorithms for high-dimensional problems like neural architecture search?

High-dimensional spaces require specialized approaches:

- Use contextual bandits that incorporate state information using algorithms like LinUCB [18].

- Implement hierarchical strategies that group similar options together [19].

- Apply Thompson Sampling with probabilistic models that capture parameter distributions [15].

- Leverage population-based guidance as in PBG, which uses the current population distribution to guide mutations toward unexplored regions [7].

FAQ 4: What are the computational complexity tradeoffs between different MAB algorithms?

Table: Computational Complexity of Common MAB Algorithms

| Algorithm | Time Complexity | Space Complexity | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| ε-Greedy | O(1) per selection | O(k) for k arms | Simple environments with limited arms [15] |

| Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) | O(k) per selection | O(k) | Stationary environments with clear uncertainty bounds [15] |

| Thompson Sampling | O(k) per selection | O(k) for parameters | Problems with natural conjugate priors [15] |

| LinUCB (Contextual) | O(d²) per selection | O(d²) for d features | High-dimensional contexts with linear reward structures [18] |

FAQ 5: How can I translate principles from neural population dynamics to improve my optimization algorithms?

Implement strategies inspired by brain neuroscience:

- Attractor trending: Drive solutions toward stable, high-reward states (exploitation) [3].

- Coupling disturbance: Introduce controlled disruptions to escape local optima (exploration) [3].

- Information projection: Regulate information flow between solution populations to balance tradeoffs [3].

- Neural-inspired randomization: Mimic neural variability patterns rather than using uniform random noise [5].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Rapid Performance Plateaus in Evolutionary Neural Architecture Search

Symptoms: Initial improvement followed by extended periods without meaningful progress; population diversity drops below 5%.

Diagnosis: Premature convergence due to over-exploitation.

Solution Protocol:

- Immediate action: Implement guided mutation using Population-Based Guiding (PBG):

- Parameter adjustment: Increase mutation rate by 30-50% temporarily.

- Strategy enhancement: Add ε-decay schedule starting with ε=0.2 and reducing to 0.01 over 70% of iterations [7].

Issue: High Variance in MAB Algorithm Performance Across Trials

Symptoms: Inconsistent results between runs with identical parameters; unpredictable convergence patterns.

Diagnosis: Insufficient exploration or overly sensitive reward structures.

Solution Protocol:

- Stabilization: Implement reward normalization:

- Algorithm selection: Switch to Thompson Sampling for better uncertainty quantification:

- Validation: Conduct statistical significance testing with at least 30 independent runs [15] [17].

Issue: Prohibitive Computational Costs in Large Search Spaces

Symptoms: Experiment runtime growing exponentially with problem dimension; resource constraints limiting exploration.

Diagnosis: Inefficient sampling strategy scaling poorly with dimensionality.

Solution Protocol:

- Dimensionality reduction: Implement feature hashing or embedding projections.

- Parallelization: Use distributed evaluation frameworks (e.g., Ray or Spark) for population-based methods.

- Adaptive allocation: Implement the MAB-OS framework to dynamically select optimizers:

- Early stopping: Implement heuristic pruning of poorly performing arms/solutions after statistical validation [19].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Benchmarking Exploration-Exploitation Strategies

Purpose: Systematically compare the performance of different exploration strategies in neural population algorithms.

Materials:

- Standard benchmark functions (Sphere, Rastrigin, Ackley)

- Neural Population Dynamics Optimization Algorithm (NPDOA) implementation [3]

- Multi-Armed Bandit test suite with known reward distributions [15]

Methodology:

- Initialization:

- Set population size to 50 for neural algorithms

- Configure 10 arms for MAB problems with Gaussian rewards

- Define evaluation budget: 10,000 function evaluations

Experimental conditions:

Data collection:

- Record reward at each iteration

- Track population diversity every 100 iterations

- Measure cumulative regret relative to optimal

- Document computational time per iteration

Analysis:

- Perform ANOVA across conditions with post-hoc testing

- Calculate effect sizes for significant differences

- Generate learning curves with confidence intervals

Protocol 2: Hybrid MAB-Metaheuristic Framework for Drug Discovery

Purpose: Optimize molecular design using a hybrid approach combining bandit-based selection with population-based search.

Materials:

- Chemical compound library with property predictions

- QSAR models for activity prediction

- Implementation of MAB-OS framework [19]

- NPDOA or PBG algorithm [3] [7]

Methodology:

- Problem formulation:

- Define arms as different molecular optimization strategies

- Represent molecules in continuous latent space

- Set reward as predicted binding affinity

Hybrid algorithm integration:

Diagram Title: Hybrid MAB-Metaheuristic Drug Optimization

Parameter settings:

- MAB-OS with HHO, DE, and WOA as base optimizers [19]

- Population size: 100 molecules

- Iteration budget: 500 generations

- Evaluation metric: Multi-objective (affinity, solubility, toxicity)

Validation:

- Compare against single-algorithm baselines

- Statistical testing with Bonferroni correction

- Computational efficiency analysis

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table: Key Computational Components for Exploration-Exploitation Research

| Component | Function | Example Implementations |

|---|---|---|

| Neural Population Simulator | Models interconnected neural dynamics for bio-inspired optimization | NPDOA with attractor trending, coupling disturbance, information projection [3] |

| Bandit Algorithm Library | Provides implementations of various MAB strategies | ε-Greedy, UCB, Thompson Sampling, LinUCB [15] [18] |

| Optimizer Selection Framework | Dynamically chooses best algorithm during optimization | MAB-OS with HHO, DE, WOA as base algorithms [19] |

| Population Diversity Metrics | Quantifies exploration in evolutionary algorithms | Genotype diversity, entropy measures, novelty detection [7] |

| Reward Shaping Tools | Transforms raw outputs to facilitate learning | Normalization, whitening, relative advantage calculation [15] |

| Convergence Detection | Identifies stabilization points in optimization | Statistical tests, slope analysis, diversity thresholds [3] |

Advanced Visualization Frameworks

Neural Population Dynamics Optimization Algorithm Workflow

Diagram Title: NPDOA Exploration-Exploitation Balance

Multi-Armed Bandit Decision Process

Diagram Title: MAB Decision Cycle

Performance Benchmarking Tables

Table: Neural Algorithm Comparison on Standard Benchmarks

| Algorithm | Average Convergence Iterations | Success Rate (%) | Diversity Maintenance | Computational Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NPDOA | 1,250 | 94.5 | High | Medium [3] |

| Genetic Algorithm | 2,100 | 87.2 | Medium | High [3] |

| Particle Swarm | 1,800 | 89.7 | Medium | Low [3] |

| PBG (Population-Based Guiding) | 1,100 | 96.1 | High | Medium [7] |

Table: MAB Algorithm Performance Characteristics

| Algorithm | Cumulative Regret | Simple Problems | Complex Problems | Implementation Complexity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ε-Greedy | Medium | Excellent | Good | Low [15] |

| Upper Confidence Bound | Low | Good | Excellent | Medium [15] |

| Thompson Sampling | Low | Good | Excellent | High [15] |

| LinUCB (Contextual) | Low | Fair | Excellent | High [18] |

The Role of Population Diversity as a Key Indicator of Algorithm Health

Frequently Asked Questions

What is population diversity in the context of optimization algorithms? Population diversity refers to the variety of genetic material or solution characteristics present within a population of candidate solutions in a meta-heuristic algorithm. In neural population algorithms, this can be measured by the differences in the neural states or firing rates of neurons across the population [3]. High diversity indicates that the algorithm is exploring a wide area of the search space.

Why is population diversity a critical indicator of algorithm health? Diversity is a direct measure of the balance between exploration (searching new areas) and exploitation (refining known good areas). A significant loss of diversity often leads to premature convergence, where the algorithm gets stuck in a local optimum and cannot find the global best solution [3] [20]. Monitoring it allows researchers to diagnose poor performance.

What are the common symptoms of low population diversity? Key symptoms include:

- Rapid convergence of all population members to nearly identical solutions.

- A stagnation in the improvement of the best-found solution over many iterations.

- The population's average fitness closely matching the best individual's fitness.

- In neural population dynamics, this may manifest as highly correlated neural states across different populations [21].

How can I measure population diversity in my experiments? Diversity can be quantified using several metrics, summarized in the table below. For neural populations, information-theoretic measures derived from neural activity correlations are also highly effective [21].

What strategies can I use to restore and maintain population diversity? Strategies include introducing coupling disturbances between sub-populations, using guided mutation to steer the search toward unexplored regions, and implementing information projection to control communication between populations [3] [7]. Explicitly increasing population size or resampling can also help, particularly in noisy optimization environments [20].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Premature Convergence

The algorithm converges quickly to a solution that is clearly not the global optimum.

| Diagnostic Step | Action |

|---|---|

| Measure Diversity | Calculate the average Euclidean distance between solutions in the population over iterations. A steady, rapid decline confirms the issue. |

| Check Strategy Balance | Review the parameters controlling exploration (e.g., mutation rate, disturbance strength) versus exploitation (e.g., selection pressure, attractor trend). |

| Visualize the Population | Project the population into a 2D or 3D space (using PCA or t-SNE) over time. The points will cluster tightly very early on. |

Solution Protocols:

- Introduce a Coupling Disturbance: As implemented in the Neural Population Dynamics Optimization Algorithm (NPDOA), deliberately disrupt the trend of neural populations towards attractors by coupling them with other populations. This strategy directly improves exploration [3].

- Implement Guided Mutation: Use a method like Population-Based Guiding (PBG). This involves calculating the distribution of genes (e.g., network connections or operations) in the current population and mutating genes toward less frequent values. This encourages exploration of underrepresented areas of the search space [7].

- Increase Behavioral Variability (Random Exploration): Inject noise into the value estimates or decision-making process of the algorithm. This can be as simple as increasing the "temperature" in a softmax selection rule or using an adaptive method like Thompson Sampling [5].

Problem 2: Population Dispersion Failure

The population fails to concentrate around high-quality solutions, even after extensive iterations, resulting in slow or ineffective optimization.

| Diagnostic Step | Action |

|---|---|

| Verify Exploitation Mechanisms | Ensure that your selection and attraction mechanisms are functioning correctly. An overly strong exploration strategy can prevent convergence. |

| Evaluate in a Noise-Free Environment | Test the algorithm on a clean, synthetic benchmark problem. If performance improves, the issue may be related to noise handling. |

| Inspect Fitness-Population Correlation | Analyze if individuals with higher fitness are being successfully selected to guide the population. A lack of correlation indicates weak exploitation. |

Solution Protocols:

- Enhance Attractor Trending: Strengthen the mechanisms that drive populations toward optimal decisions. In NPDOA, the attractor trending strategy is responsible for ensuring exploitation capability [3].

- Apply a Greedy Selection Operator: Implement a selection process that prioritizes the best-performing individuals (or pairs of individuals) for reproduction. This greedily exploits current knowledge to refine solutions [7].

- Use an Information Projection Strategy: Regulate the communication and influence between different neural populations. This strategy helps transition the algorithm from a global exploration phase to a local exploitation phase [3].

Experimental Protocols for Measuring Diversity

Protocol 1: Genotypic Diversity Measurement

This protocol measures diversity based on the direct encoding of the solutions.

- Encoding: Represent each individual in the population of size

Nas a vector in a D-dimensional space. - Calculation: Compute the pair-wise Euclidean distance between every individual in the population.

- Averaging: The population's genotypic diversity is the average of all these pairwise distances.

- Formula:

- Let

Pbe the population ofNindividuals. - Diversity = ( \frac{2}{N(N-1)} \sum{i=1}^{N-1} \sum{j=i+1}^{N} || Pi - Pj || )

- Let

Protocol 2: Phenotypic & Information-Theoretic Measurement

This protocol is ideal for neural population algorithms and measures diversity based on the activity or output of the systems.

- Record Activity: For each individual in the population, record the firing rate vector or decision output in response to a standard set of inputs or at a specific time in the trial.

- Analyze Correlations: Calculate the pairwise correlation coefficients of the activity vectors across the population.

- Quantify Diversity: A population with high diversity will show a mix of positive and negative correlations, or low average correlation. The presence of structured correlation motifs (like information-enhancing hubs) can be a sign of healthy, specialized population codes [21].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Solution | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Neural Population Dynamics Optimization Algorithm (NPDOA) | A brain-inspired meta-heuristic framework that explicitly models attractor trending, coupling disturbance, and information projection to balance exploration and exploitation [3]. |

| Population-Based Guiding (PBG) | An evolutionary framework for Neural Architecture Search that uses greedy selection and guided mutation to control population diversity and search efficiency [7]. |

| Vine Copula Models | A statistical multivariate modeling tool used to accurately estimate mutual information and complex, nonlinear dependencies in neural population data, controlling for confounding variables like movement [21]. |

| Dispatching Rules (DRs) | Simple, fast constructive heuristics used to initialize the population of a genetic algorithm, providing high-quality starting points that improve convergence speed and final performance [22]. |

| Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) Algorithm | A policy for directed exploration that adds an "information bonus" to the value of an option based on its uncertainty, systematically driving exploration [5]. |

| Thompson Sampling | A strategy for random exploration that scales decision noise with the agent's uncertainty, leading to high exploration initially that decreases over time to facilitate exploitation [5]. |

Conceptual Diagram: Balancing Exploration & Exploitation

The following diagram illustrates the core strategies and their role in maintaining a healthy exploration-exploitation balance through population diversity, as inspired by neural population and evolutionary algorithms.

Experimental Workflow: Diagnosing Algorithm Health

This workflow outlines the steps for a researcher to systematically diagnose and correct the health of a neural population or evolutionary algorithm.

Advanced Algorithms and Their Biomedical Applications: From PBG to Drug Design

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the core innovation of the Population-Based Guiding (PBG) framework?

The core innovation of PBG is its novel guided mutation approach, which uses the current population's distribution to automatically steer the search process. Unlike traditional methods that rely on fixed, hand-tuned mutation rates, PBG calculates mutation probabilities based on whether a specific architectural feature (encoded in a binary vector) is common (probs1) or rare (probs0) within the current population. Sampling from probs0 encourages exploration of underutilized features, while the synergistic combination with an exploitative greedy selection operator effectively balances the exploration-exploitation trade-off [7].

Q2: How does PBG improve search efficiency compared to other evolutionary NAS methods? PBG improves efficiency by being up to three times faster than baseline methods like regularized evolution on benchmarks such as NAS-Bench-101. This speedup is achieved by eliminating the need for manual tuning of mutation rates and using the population itself to make informed, guided decisions on where to mutate, thus accelerating the discovery of high-performing architectures [7] [23].

Q3: My PBG search is converging to suboptimal architectures too quickly. How can I promote more exploration? Premature convergence often indicates that exploitation is overpowering exploration. You can address this by:

- Utilizing the explorative guided mutation variant (PBG-0): Ensure your implementation samples mutation indices from the

probs0vector, which directs mutations toward architectural features that are less common in the current population [7]. - Verifying the selection pressure: The greedy selection operator is highly exploitative. You can adjust the balance by modifying the selection process, for instance, by not always selecting the absolute top

npairs but incorporating a probabilistic element based on fitness rank [7] [24].

Q4: How can I integrate performance predictors to reduce the computational cost of PBG? You can integrate an ensemble performance predictor to estimate the final accuracy of a candidate architecture without full training. For example, a predictor that combines K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) regression, Random Forest (RF), and Support Vector Machine (SVM) can be trained on the performance of already-evaluated architectures. This predictor can then pre-screen new candidates, ensuring that only the most promising architectures undergo the computationally expensive full training and evaluation [24].

Q5: What are the primary hardware considerations when deploying models discovered by PBG? For deployment on resource-constrained hardware, such as satellite edge-computing chips, it is crucial to implement hardware-aware NAS. This involves embedding hardware-specific constraints—like inference latency, memory footprint, and power consumption—directly into the PBG optimization loop as additional objectives. This ensures the final model is not only accurate but also suitable for the target deployment environment [25].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Stagnating Search Performance

Problem: The population's fitness shows little to no improvement over several generations.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Loss of Population Diversity | Calculate the average Hamming distance between architecture encodings in the population. A low and decreasing value confirms this issue. | Increase the focus on exploration by switching to or increasing the rate of the PBG-0 (probs0) guided mutation variant [7]. |

| Ineffective Crossover | Analyze if offspring performance is consistently worse than parent performance. | Review the crossover operator. Implement a simple fixed-point crossover to ensure valid architectures are produced, and consider if a more sophisticated method is needed for your search space [7]. |

| Weak Selection Pressure | Check if the fitness variance in the population is low. The greedy selection may not be focusing enough on the best performers. | Ensure the greedy selection operator is correctly implemented, selecting parent pairs based on the sum of their fitness scores to promote the recombination of strong candidates [7]. |

Issue 2: High Computational Overhead per Evaluation

Problem: The time taken to train and evaluate each candidate architecture is prohibitive, limiting the total number of search iterations.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Full Training is Too Long | The architecture is being trained to convergence for evaluation. | Adopt a multi-fidelity evaluation strategy. Use lower-fidelity approximations like training for fewer epochs, on a smaller dataset, or at a lower resolution to quickly filter out poor candidates [26]. |

| Lack of Performance Prediction | Every new architecture is sent for full training. | Integrate an ensemble performance predictor (e.g., based on KNN, RF, and SVM) to act as a proxy for the true performance, reserving full training only for top-ranked candidates [24]. |

| Search Space is Too Large | The genotype encoding is excessively long, leading to a vast search space. | Re-design the search space to incorporate sensible prior knowledge and expert blocks, which can constrain the space to more promising regions and reduce the number of invalid or poor architectures [24]. |

Experimental Protocols & Performance Data

Key Experiment: Benchmarking on NAS-Bench-101

Objective: To evaluate the performance and efficiency of PBG against established evolutionary NAS baselines.

Methodology:

- Search Space: Utilize the standard NAS-Bench-101 cell-based search space.

- Population Initialization: Initialize a population of neural network architectures with random configurations.

- Evolutionary Loop: For each generation:

a. Greedy Selection: Generate all possible parent pairings (excluding self-pairing) and select the top

npairs based on the highest sum of validation accuracies [7]. b. Crossover: Apply a fixed-point crossover operator to selected parent pairs to produce offspring. c. Guided Mutation: Apply the guided mutation operator (both PBG-1 and PBG-0 variants tested) to the offspring. The mutation indices are sampled based on the probability vectors (probs1orprobs0) derived from the current population's one-hot encoding [7]. d. Evaluation: Train and evaluate new candidate architectures on the CIFAR-10 dataset (or use the pre-computed performance in NAS-Bench-101). - Termination: The search concludes after a fixed number of generations or when performance plateaus.

Quantitative Results: The following table summarizes the expected performance of PBG compared to other methods on the NAS-Bench-101 benchmark.

| Method | Key Principle | Best Found Accuracy (%) | Time to Target Accuracy (x faster) |

|---|---|---|---|

| PBG (Proposed) | Guided mutation + Greedy selection | ~94.5 | 3x (baseline) |

| Regularized Evolution | Evolution with aging | ~94.2 | 1x (baseline) |

| Random Search | Uniform random sampling | ~93.8 | >3x (slower) |

| MPE-NAS [24] | Multi-population evolution | Comparable / Superior on specific classes | Varies (improves other EC-based methods) |

Workflow Diagram: PBG Framework

Detailed Diagram: Guided Mutation Operation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table details key computational tools and concepts essential for implementing and experimenting with the PBG framework.

| Item Name | Function / Explanation | Relevance to PBG |

|---|---|---|

| NAS-Bench-101 | A tabular benchmark containing pre-computed performance of 423k neural cell architectures within a fixed search space. | Serves as a standard benchmark for quick and reproducible validation of PBG's performance and efficiency claims [7]. |

| Greedy Selection Operator | A selection mechanism that generates all possible parent pairings and selects the top n pairs based on the sum of their fitness. |

The primary driver for exploitation in PBG, ensuring the best genetic material is recombined [7]. |

| Guided Mutation (probs0) | A mutation operator that samples mutation locations from an inverted probability vector (probs0), favoring features underrepresented in the population. |

The primary driver for exploration in PBG, steering the search toward novel and unexplored regions of the architecture space [7]. |

| Ensemble Performance Predictor | A meta-model (e.g., combining KNN, RF, SVM) that predicts the final performance of an untrained architecture based on its encoding. | Dramatically reduces computational cost by acting as a cheap proxy for expensive full training during the search [24]. |

| Hardware-in-the-Loop Profiler | Tools that measure real-world metrics like inference latency and memory usage of a model on target hardware (e.g., NVIDIA Jetson). | Enables hardware-aware NAS, allowing PBG to be extended to optimize for deployment constraints like power and latency, crucial for edge devices [25]. |

Greedy Selection for Intensification (Exploitation) and Guided Mutation for Diversification (Exploration)

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental trade-off in evolutionary algorithms, and how do greedy selection and guided mutation address it? The core trade-off is between exploitation (refining known good solutions) and exploration (searching for new, potentially better solutions). Greedy selection intensifies the search by exploiting the best current solutions, while guided mutation diversifies the population by exploring new areas of the search space. Balancing these two processes is crucial for avoiding premature convergence and finding the global optimum [3] [7].

Q2: How does the greedy selection algorithm work in the NPDOA framework? In the Neural Population Dynamics Optimization Algorithm (NPDOA), a specific greedy selection process is used:

- It generates all possible pairings from a population of

nindividuals, excluding self-pairings, resulting inn(n-1)/2combinations. - Each pair is assigned a score by summing the fitness values of the two individuals.

- The top

npairings with the highest combined fitness scores are selected for reproduction. This method differs from traditional approaches by selecting the best combinations of individuals rather than just the best individuals, which helps maintain diversity while focusing on high performance [7].

Q3: What is the role of guided mutation, and how does it promote exploration?

Guided mutation steers the evolutionary search toward less explored regions of the search space. In the Population-Based Guiding (PBG) framework, a guided mutation algorithm uses the current population's distribution to propose mutation indices. It calculates the probability of a feature being '1' or '0' across the population and then samples mutation locations from the inverted probability vector (probs0). This makes it more likely to mutate features that are uncommon in the current population, thereby fostering exploration and reducing the chance of getting stuck in local optima [7].

Q4: In what practical domains are these algorithms particularly relevant? These advanced evolutionary strategies are highly relevant in fields that involve complex optimization problems, such as:

- Drug Discovery: For optimizing drug design, predicting drug-target interactions, and designing clinical trials [27] [28].

- Neural Architecture Search (NAS): For automatically discovering high-performing neural network architectures [7].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Premature Convergence

Problem: The algorithm converges too quickly to a sub-optimal solution, lacking diversity in the final population.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Check | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Overly aggressive exploitation | Check if population diversity drops rapidly in early generations. | Increase the influence of the guided mutation strategy (e.g., use the PBG-0 variant) to explore less-visited regions [7]. |

| Weak exploration pressure | Analyze if mutation rates are too low or not informed by population diversity. | Implement a guided mutation approach that uses the inverted population probability (probs0) to actively target unexplored genetic material [7]. |

Issue 2: Low Computational Efficiency

Problem: The algorithm requires too many generations or evaluations to find a satisfactory solution.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Check | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Inefficient balance of strategies | Monitor the ratio of successful explorations vs. exploitations over time. | Ensure a synergistic balance between greedy selection (for fast intensification) and guided mutation (for effective diversification) as seen in the PBG framework [7]. |

| High-dimensional search spaces | Evaluate performance on benchmark problems with similar dimensions. | Leverage algorithms like NPDOA, which are designed with strategies like attractor trending and coupling disturbance to handle complex spaces efficiently [3]. |

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: Implementing Population-Based Guiding (PBG) for Neural Architecture Search

This protocol outlines the steps to implement the PBG framework, which combines greedy selection and guided mutation [7].

1. Algorithm Initialization:

- Initialize a population of candidate architectures.

- Encode each architecture into a genotype, typically using a categorical one-hot encoding.

2. Greedy Selection Phase:

- Evaluate all individuals in the population to determine their fitness (e.g., model accuracy).

- Generate all possible non-repeating pairings from the population.

- For each pair, calculate a combined fitness score by summing the individual fitness values.

- Select the top

npairs with the highest combined scores for reproduction.

3. Crossover and Guided Mutation Phase:

- Crossover: For each selected pair, perform crossover by randomly sampling a crossover point to create offspring.

- Guided Mutation:

- Flatten the one-hot encoded genotypes of the entire current population.

- Sum the values for each genetic index across the population and average them to create a probability vector,

probs1, where each element represents the frequency of a '1' at that index. - Calculate the inverse vector,

probs0 = 1 - probs1. - For each offspring, sample a mutation index based on the

probs0distribution. This biases mutations toward features that are less common in the population. - Mutate the selected index in the offspring's genotype.

4. Iteration:

- The new offspring form the next generation.

- Repeat the process from step 2 until a termination criterion is met (e.g., a maximum number of generations or a performance threshold).

Protocol 2: Applying Evolutionary Strategies in AI-Driven Drug Discovery

This protocol describes how evolutionary algorithms can be integrated into the drug discovery pipeline [27] [28].

1. Problem Formulation:

- Define the Objective: The goal could be to design a small molecule with desired properties, such as high binding affinity to a target protein, low toxicity, and optimal pharmacokinetics.

- Representation: Define a meaningful encoding for drug molecules (e.g., as a SMILES string or a molecular graph).

2. Fitness Evaluation:

- Use machine learning models (e.g., supervised learning or deep learning) as surrogate models to predict the properties of a candidate molecule. This avoids costly wet-lab experiments for every candidate [28].

- Common predictive tasks include virtual screening, drug-target interaction prediction, and ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, Toxicity) forecasting [27].

3. Evolutionary Optimization:

- Apply an evolutionary algorithm, such as one employing greedy selection and guided mutation, to evolve a population of candidate molecules.

- The fitness function is the output of the ML-based surrogate models.

- The algorithm iteratively generates new molecules through selection, crossover, and mutation, aiming to maximize the fitness function.

4. Validation:

- Select the top-performing candidate molecules from the evolutionary run.

- Validate their properties through in vitro or in vivo testing in the laboratory.

Algorithm Workflow Diagrams

PBG Framework

Guided Mutation Logic

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key computational tools and strategies used in implementing algorithms like NPDOA and PBG.

| Research Reagent / Component | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Fitness Function | A metric (e.g., model accuracy, drug binding affinity) that evaluates the quality of a candidate solution and guides the selection process [7]. |

| Population Genotype | The encoded representation (e.g., one-hot vector) of all individuals in a generation, enabling the application of genetic operators [7]. |

| Greedy Selection Operator | A selection strategy that exploits high-performing areas of the search space by prioritizing the best candidate pairs for reproduction based on their combined fitness [7]. |

| Guided Mutation (probs0) | An exploration strategy that diversifies the search by mutating solution features that are currently rare in the population, using an inverted probability vector [7]. |

| Surrogate ML Model | In drug discovery, a machine learning model used to quickly predict the properties of candidate molecules, acting as a computationally efficient proxy for lab experiments [27] [28]. |

| Neural Population Dynamics | A brain-inspired model that simulates the interaction of neural populations to balance decision-making (exploitation) and adaptation to new information (exploration) [3]. |

The challenge of balancing exploration (searching new, unknown regions) and exploitation (refining known, promising areas) is a fundamental dilemma in optimization and search algorithms [5]. In the context of molecular discovery, this translates to the need for strategies that can efficiently navigate the astronomically vast chemical space, estimated to contain over 10^60 synthetically feasible small molecules [29]. Traditional evolutionary algorithms in drug discovery often rely on random mutation, which can be inefficient for exploring this immense landscape. This case study examines how guided mutation strategies, inspired by principles from neural population dynamics research, can direct molecular exploration toward uncharted and potentially fruitful regions of chemical space, thereby achieving a more effective balance between exploration and exploitation.

Theoretical Foundation: Exploration-Exploitation in Algorithm Design

Core Strategies for Balancing Exploration and Exploitation

Research in cognitive science and neuroscience has identified two primary strategies that humans and animals use to solve the explore-exploit dilemma, which provide a framework for algorithm design [5]:

Directed Exploration: This strategy involves an explicit, calculated bias toward more informative options. In computational terms, this is often implemented by adding an information bonus to the value of an action based on its potential for knowledge gain. Algorithms like Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) epitomize this strategy by setting the information bonus proportional to the uncertainty about the expected payoff from each option [5].

Random Exploration: This approach introduces stochasticity through decision noise that drives exploration by chance. Mathematically, this can be implemented by adding zero-mean random noise to value computations before selecting the action with the highest resultant value. The softmax choice function and Thompson Sampling are examples of this strategy [5].

These strategies are not mutually exclusive and can be effectively combined in holistic approaches. Evidence suggests they have distinct neural implementations, with directed exploration associated with prefrontal structures and mesocorticolimbic regions, while random exploration may be modulated by catecholamines like norepinephrine and dopamine [5].

Neural Population Dynamics as Inspiration

The Neural Population Dynamics Optimization Algorithm (NPDOA) provides a brain-inspired meta-heuristic framework that implements three key strategies relevant to molecular search [3]:

- Attractor Trending Strategy: Drives neural populations (solutions) toward optimal decisions, ensuring exploitation capability.

- Coupling Disturbance Strategy: Deviates neural populations from attractors through coupling with other neural populations, improving exploration ability.

- Information Projection Strategy: Controls communication between neural populations, enabling a transition from exploration to exploitation.

This framework demonstrates how biological principles can inform the design of algorithms that dynamically balance exploration and exploitation, rather than relying on static balances.

Guided Mutation: Core Methodologies and Workflows

Population-Based Guiding (PBG) for Evolutionary Neural Architecture Search

The Population-Based Guiding (PBG) framework implements a guided mutation approach that synergizes explorative and exploitative methods [7]. This method uses the current population's distribution to inform mutation locations, eliminating the need for manual tuning of mutation rates.

Key Components of PBG:

- Greedy Selection: Promotes exploitation by selecting the best parent pairs based on combined fitness scores for reproduction. This method generates all possible pairings from a population of n individuals, excludes self-pairing and permutations, and selects the top n pairings with the highest combined fitness scores [7].

- Random Crossover: Maintains a balance between randomness and reuse of established components through fixed-point crossover by randomly sampling a crossover point.

- Guided Mutation: Steers the population toward exploring new territories by using the current population to propose mutation indices.

Table: PBG Guided Mutation Algorithm Variants

| Variant | Probability Source | Strategy | Effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| PBG-1 | probs1 (direct population vector) | Exploitation | Applies Proximate Optimality Principle, assuming similar solutions have similar fitness |

| PBG-0 | probs0 (inverted population vector) | Exploration | Encourages exploration of less-visited regions of the search space |

The guided mutation process can be visualized through the following workflow:

TRIAD: Transposition-Based Random Insertion and Deletion Mutagenesis

In directed enzyme evolution, the TRIAD (Transposition-based Random Insertion And Deletion mutagenesis) approach provides a biological implementation of guided exploration [30]. Unlike traditional point mutagenesis, TRIAD generates libraries of random variants with short in-frame insertions and deletions (InDels), accessing functional innovations and traversing unexplored fitness landscape regions.

TRIAD Workflow:

- Transposition Reaction: An in vitro Mu transposition reaction using engineered mini-Mu transposons (TransDel for deletions, TransIns for insertions) randomly inserts transposons within the target DNA sequence.

- Library Generation:

- For deletions: MlyI restriction enzyme digestion removes specific sequences, generating -3, -6, or -9 bp deletions.

- For insertions: Custom shuttle cassettes (Ins1, Ins2, Ins3) with randomized nucleotide triplets are ligated, then removed with AcuI digestion, leaving +3, +6, or +9 bp insertions.

- Library Quality Assessment: Sequencing validates library diversity and distribution.

Table: TRIAD Library Characteristics for Phosphotriesterase Evolution

| Library Type | Theoretical Max Diversity | Unique Variants Detected | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| -3 bp Deletion | ~1000 | >10^3 | Only 4% frameshifts |

| +3 bp Insertion | 6.4 × 10^4 | >10^5 | 95% of DNA positions accessed |

| +6 bp Insertion | ~4.1 × 10^6 | >10^5 | 80% of positions had ≥10 distinct insertions |

| +9 bp Insertion | ~2.6 × 10^8 | >10^5 | Different functional profiles emerged |

The following diagram illustrates the complete TRIAD workflow for generating both deletion and insertion libraries:

ACSESS: Algorithm for Chemical Space Exploration with Stochastic Search

For exploring the small molecule universe (SMU), the ACSESS algorithm combines stochastic chemical structure mutations with methods for maximizing molecular diversity [29]. This approach fundamentally differs from traditional chemical genetic algorithms by enabling rigorous exploration of astronomically large chemical spaces without exhaustive enumeration.

ACSESS Generation Cycle:

Reproduction and Mutation:

- Crossover Mutation: Two parent compounds are split by cutting random acyclic bonds, and fragments are recombined.

- Chemical Mutations: Addition/removal of atoms, creation/removal of ring bonds, modification of atom type or bond order.

Filtering: Compounds outside the target chemical space are removed using subgroup filters, steric strain filters, and physiochemical filters.

Maximally Diverse Subset Selection: The library size is reduced by selecting a maximally diverse subset using either the "maximin" algorithm or cell-based diversity definition, ensuring diversity improvement each generation.

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Guided Mutation Experiments

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Our guided mutation algorithm is converging prematurely to local optima. How can we enhance exploration?

A: Implement the PBG-0 variant that samples mutation indices from the inverted population vector (probs0) rather than the direct vector [7]. This explicitly directs mutations toward less-explored regions of the search space. Additionally, consider increasing the influence of the coupling disturbance strategy inspired by neural population dynamics, which deliberately deviates solutions from current attractors to improve exploration [3].

Q2: How can we quantify and track the exploration-exploitation balance during our molecular search experiments?

A: Monitor these key metrics:

- Population Diversity: Calculate the average nearest-neighbor distance in chemical descriptor space or the number of occupied cells in a discretized chemical space [29].

- Novelty Rate: Track the proportion of newly generated structures that are significantly different from previous generations (e.g., using Tanimoto similarity <0.7).

- Exploration-Exploitation Ratio: For algorithms like NPDOA, measure the relative influence of attractor trending (exploitation) versus coupling disturbance (exploration) strategies across generations [3].

Q3: Our mutation strategies are producing predominantly non-viable molecular structures. How can we improve validity rates?

A: Implement sequential graph-based building approaches with validity guarantees, as used in EvoMol [31]. By filtering invalid actions at every step and working with molecular graphs rather than SMILES strings, you can ensure all intermediate and final molecules are valid. Additionally, incorporate chemical feasibility filters similar to those in ACSESS, which remove compounds with reactive labile moieties or excessive steric strain [29].

Q4: How do we adapt guided mutation approaches for very large search spaces with computationally expensive fitness evaluations?

A: Employ a multi-fidelity optimization approach:

- Use fast, approximate property predictors (like machine learning models) for initial screening [32].

- Apply guided mutation to generate promising candidates based on these predictions.

- Validate top candidates with high-fidelity, computationally intensive methods (e.g., DFT calculations) [33].

- Incorporate these results back into the model to refine future predictions.

Q5: What strategies can help escape from previously explored regions when a search has stagnated?

A: Implement a horizon-dependent exploration strategy [5]. When stagnation is detected:

- Temporarily increase the weight of the exploration component (e.g., coupling disturbance in NPDOA [3] or PBG-0 in Population-Based Guiding [7]).

- Introduce completely novel seed molecules from underrepresented regions of chemical space.

- Temporarily broaden chemical mutation rules to allow more dramatic structural changes, similar to the extensive mutation set in EvoMol [31].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Computational Tools for Guided Mutation Experiments

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| mmpdb (Python package) | Matched molecular pair analysis | Deriving mutagenicity transformation rules from structural changes [32] |

| RDKit | Cheminformatics and molecular manipulation | Sanity testing molecules, generating molecular descriptors, and graph-based operations [31] |

| Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) | Learning on graph-structured data | Modeling materials at atomic level, predicting molecular properties [33] |

| TRIAD Molecular Biology Kit | Transposon-based mutagenesis | Generating random InDel libraries for enzyme evolution [30] |

| ACSESS Framework | Chemical space exploration | Generating representative universal libraries spanning diverse chemistries [29] |

Guided mutation represents a powerful paradigm for addressing the fundamental exploration-exploitation dilemma in molecular search. By learning from current population distributions and strategically directing mutations toward unexplored regions, these approaches enable more efficient navigation of vast chemical spaces. The integration of insights from neural population dynamics provides a biologically-inspired framework for dynamically balancing exploratory and exploitative tendencies. As demonstrated across diverse applications from enzyme engineering to small molecule discovery, guided mutation strategies can access novel functional regions of sequence space that remain inaccessible to traditional random mutagenesis approaches. Continued development of these methodologies, particularly through hybrid approaches combining multiple exploration strategies, promises to further accelerate molecular discovery across biomedical and materials science domains.

Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ 1: What types of surrogate models are most suitable for integration with neural population algorithms? The choice of surrogate model depends on the specific needs of the metaheuristic and the nature of the optimization task. The three fundamental approximation types are [34]:

- Regression Models: These directly approximate the exact value of the computationally expensive objective function, enabling precise comparisons between candidate solutions. Examples include Radial Basis Functions (RBF) and Gaussian Processes (GPR/Kriging) [34] [35].

- Classification Models: These categorize solutions into classes (e.g., "promising" or "non-promising") instead of predicting exact fitness values, which can be sufficient for selection procedures in some algorithms [34].

- Ranking Models: These focus on predicting the relative order of solutions rather than their absolute quality, which aligns well with rank-based selection mechanisms used in many metaheuristics [34].

For neural population algorithms, local surrogate models (like RBF) built from the nearest neighbors of the current best solutions are often effective, as they can finely approximate the landscape in promising regions [35].

FAQ 2: How can I prevent my surrogate-assisted neural algorithm from converging prematurely to a local optimum? Premature convergence often indicates an imbalance where exploitation overpowers exploration. To address this [35] [3]:

- Implement a Hybrid Algorithm: Combine the neural population algorithm with another metaheuristic that has strong exploratory capabilities. For instance, the Gannet Optimization Algorithm (GOA) can be hybridized with the Differential Evolution (DE) algorithm, using a control strategy to switch between them based on search progress [35].

- Use an Ensemble of Surrogates: Relying on a single surrogate model can introduce bias. Using multiple models or an ensemble can provide a more robust approximation and reduce the risk of being misled by an inaccurate model [34].

- Incorporate a Restart Strategy: A generation-based optimal restart strategy can help the algorithm jump out of local optima. This involves using some of the best samples to construct local surrogate models and restart the search from these points [35].

FAQ 3: What are the best strategies for managing the computational budget when training surrogate models? Efficient sample management is critical. Key strategies include [34] [35]:

- Adaptive Sampling (Add-point strategy): Instead of using a static set of samples, use an adaptive strategy that selects new points for expensive evaluation based on the current surrogate model. This focuses the computational budget on evaluating the most promising or informative candidates. One effective method is a strategy based on historical surrogate model information [35].

- Static Sampling for Initialization: Begin with a space-filling static sampling method, like Latin Hypercube Sampling (LHS), to build an initial surrogate model that coarsely covers the entire search space [35].

FAQ 4: In pharmaceutical applications like drug discovery, how are surrogate models validated to ensure reliability? In computationally expensive fields like drug discovery, validation is crucial [36] [37]:

- Benchmarking Sets: Models are tested against established benchmarking sets, such as DUD-E, which contains diverse active binders and decoys for different protein targets [36].

- Performance Metrics: Throughput (time to score a set of ligands) and accuracy (e.g., Spearman rank correlation between predicted and actual binding affinities) are key quantitative metrics [36].

- Uncertainty Quantification (UQ): Integrating UQ with surrogate models, such as Graph Neural Networks (GNNs), allows the model to assess its own prediction reliability. This helps in deciding when to trust the surrogate's predictions and when to fall back on an expensive simulation, guiding a more reliable exploration of the chemical space [37].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: The algorithm is not finding better solutions, even with the surrogate model.

- Potential Cause 1: Inaccurate Surrogate Model. The model is failing to accurately approximate the true fitness landscape, particularly in unexplored regions.

- Solution: Incorporate Uncertainty Quantification (UQ). Use a surrogate model that provides uncertainty estimates for its predictions. Guide the search using acquisition functions like Probabilistic Improvement (PIO), which selects candidates based on the likelihood they will exceed a performance threshold, balancing the use of promising areas (exploitation) with uncertain regions (exploration) [37].

- Potential Cause 2: Poor Balance Between Exploration and Exploitation. The algorithm is either wandering randomly or has converged too quickly.

- Solution: Explicitly design strategies for both phases. The Neural Population Dynamics Optimization Algorithm (NPDOA) offers a brain-inspired framework with three core strategies [3]:

- Attractor Trending Strategy: Drives the population towards optimal decisions (exploitation).

- Coupling Disturbance Strategy: Deviates populations from attractors to explore new areas (exploration).

- Information Projection Strategy: Controls communication between populations to manage the transition from exploration to exploitation.

- Solution: Explicitly design strategies for both phases. The Neural Population Dynamics Optimization Algorithm (NPDOA) offers a brain-inspired framework with three core strategies [3]:

Problem: The overhead of building and updating the surrogate model is too high, negating its benefits.

- Potential Cause: Using an Overly Complex Model or Inefficient Sampling.

- Solution:

- Choose a Scalable Model: For high-dimensional problems, simpler models like Radial Basis Functions (RBF) can offer a good balance between accuracy and computational cost [35]. Random Forest models are also known for reduced overfitting and high efficiency [36].