Assessing Segmentation Tool Reliability for Contrast-Enhanced MRI: A Guide for Robust Neuroimaging Research

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the reliability and performance of various automated segmentation tools when applied to contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (CE-MR) scans.

Assessing Segmentation Tool Reliability for Contrast-Enhanced MRI: A Guide for Robust Neuroimaging Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the reliability and performance of various automated segmentation tools when applied to contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (CE-MR) scans. It explores the foundational challenges posed by technical heterogeneity in clinical CE-MR data and evaluates the impact of scanner and software variability on volumetric measurements. Methodological insights cover advanced deep learning approaches, such as SynthSeg+, which demonstrate high consistency between CE-MR and non-contrast scans. The content further addresses troubleshooting common pitfalls and offers optimization strategies for cross-sectional and longitudinal studies. Finally, it presents a rigorous validation and comparative framework, synthesizing performance metrics across tools to guide researchers and drug development professionals in selecting and implementing segmentation software for reliable, clinically translatable brain morphometric analysis.

The Foundational Challenge: Why CE-MR Scans Are Problematic for Automated Volumetry

Clinical brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans, including contrast-enhanced (CE-MR) images, represent a vast and underutilized resource for neuroscience research due to technical heterogeneity. These archives, accumulated through routine diagnostic procedures, contain invaluable data on brain structure and disease progression across diverse populations. However, the variability in acquisition parameters, scanner types, and imaging protocols has traditionally limited their research utility. This heterogeneity introduces confounding factors that complicate automated analysis and large-scale retrospective studies.

The reliability of morphometric measurements derived from these varied sources is paramount for producing valid scientific insights. Within this context, the development of robust segmentation tools capable of handling such heterogeneity is transforming the research landscape. Advanced deep learning approaches are now enabling researchers to extract consistent volumetric measurements from clinically acquired CE-MR images, potentially unlocking previously inaccessible datasets for neuroimaging research and drug development [1] [2]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of leading segmentation methodologies, evaluating their performance in overcoming technical heterogeneity to leverage CE-MR scans for scientific discovery.

Comparative Analysis of Segmentation Tools

Performance Benchmarking on CE-MR vs. Non-Contrast MR

The core challenge in utilizing clinical CE-MR scans lies in ensuring that volumetric measurements derived from them are as reliable as those from non-contrast MR (NC-MR) scans, which are typically acquired in controlled research settings. A direct comparative study evaluated this reliability using two segmentation tools: the deep learning-based SynthSeg+ and the more traditional CAT12 pipeline [1] [2].

Table 1: Comparative Reliability of Segmentation Tools on CE-MR vs. NC-MR Scans

| Segmentation Tool | Technical Approach | Overall Reliability (ICC) | Structures with Highest Reliability (ICC >0.94) | Structures with Notable Discrepancies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SynthSeg+ | Deep learning-based; contrast-agnostic | High (ICCs >0.90 for most structures) [1] | Larger brain structures [2] | Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and ventricular volumes [1] |

| CAT12 | Traditional pipeline; depends on intensity normalization | Inconsistent performance [1] | Information not specified | Relatively higher discrepancies between CE-MR and NC-MR [2] |

The findings indicate that SynthSeg+ demonstrates superior robustness to the variations introduced by gadolinium-based contrast agents. Its high intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) across most brain structures suggest it can reliably process CE-MR scans for morphometric analysis, making it a suitable tool for repurposing clinical archives. Inconsistent performance of CAT12 is likely due to its higher sensitivity to intensity changes, which affects its ability to generalize across different scan types [1] [2].

Tool Generalizability and Application in Disease Research

Beyond basic volumetric agreement, the value of a tool is measured by its generalizability across diverse real-world conditions and its ability to derive meaningful clinical biomarkers.

Table 2: Generalizability and Application of Segmentation Tools

| Tool / Model | Key Strength | Validation Context | Performance Metric |

|---|---|---|---|

| MindGlide | Processes any single MRI contrast (T1, T2, FLAIR, PD); efficient (<1 min/scan) [3] | Multiple Sclerosis (MS) clinical trials and routine-care data [3] | Detected treatment effects on lesion accrual and grey matter loss; Dice score: 0.606 vs. expert-labelled lesions [3] |

| MM-MSCA-AF | Multi-modal multi-scale contextual aggregation with attention fusion [4] | Brain tumor segmentation (BRATS 2020 dataset) [4] | Dice score: 0.8158 for necrotic core; 0.8589 for whole tumor [4] |

| SynthSeg Framework | Trained on synthetic data with randomized contrasts; does not require real annotated MRI data [5] | Abdominal MRI segmentation (extension of original brain model) [5] | Offers alternative when annotated MRI data is scarce; slightly less accurate than models trained on real data [5] |

The performance of MindGlide is particularly noteworthy. Its ability to work on any single contrast and its validation in detecting treatment effects in clinical trials directly addresses the thesis of repurposing heterogeneous clinical scans for research. Its higher Dice score compared to other state-of-the-art tools like SAMSEG and WMH-SynthSeg in segmenting white matter lesions further underscores the efficacy of advanced deep learning models in this domain [3].

Experimental Protocols for Benchmarking Segmentation Tools

To ensure the reliability and reproducibility of studies aiming to utilize clinical CE-MR scans, adhering to rigorous experimental methodologies is critical. The following section outlines the key protocols from cited studies.

Protocol 1: Comparative Reliability Study

This protocol is designed to directly assess the consistency of volumetric measurements between CE-MR and NC-MR scans.

- Dataset: The study utilized paired T1-weighted CE-MR and NC-MR scans from 59 clinically normal participants (age range: 21-73 years). Initially, 63 image pairs were collected, but 4 were excluded due to segmentation failures with one of the tools, highlighting a practical challenge in automated processing [2].

- Segmentation Tools: The images were processed in parallel using two segmentation tools: CAT12 (a standard SPM-based pipeline) and SynthSeg+ (a deep learning-based tool designed to be robust to contrast and scanner variations) [1] [2].

- Analysis: Volumetric measurements for various brain structures were extracted from the segmentations generated by both tools. The primary statistical analysis involved calculating Intraclass Correlation Coefficients (ICCs) to evaluate the agreement between measurements from CE-MR and NC-MR scans for the same individual. Furthermore, the utility of both scan types was evaluated by building age prediction models based on the volumetric outputs [1] [2].

Protocol 2: Validation in Clinical Trials and Real-World Data

This protocol validates a tool's performance in detecting biologically meaningful changes in heterogeneous data, which is the ultimate goal of repurposing clinical scans.

- Model Training: MindGlide was trained on a large dataset of 4,247 real MRI scans from 2,934 MS patients across 592 scanners, augmented with 4,303 synthetic scans. This extensive and varied training set is crucial for developing robustness to heterogeneity [3].

- External Validation: The model was frozen and tested on an independent external validation set comprising 14,952 scans from 1,001 patients. This set included data from two progressive MS clinical trials and a real-world routine-care paediatric MS cohort, featuring a mix of T1, T2, FLAIR, and Proton Density (PD) contrasts with diverse slice thicknesses [3].

- Outcome Measures: The model was evaluated on its ability to:

- Segment white matter lesions (compared to expert manual labels using the Dice score) [3].

- Correlate lesion load and deep grey matter volume with clinical disability scores (EDSS) [3].

- Detect statistically significant treatment effects on lesion accrual and brain volume loss in clinical trial settings [3].

Visualizing Workflows and Performance

The following diagrams illustrate the experimental workflow for benchmarking segmentation tools and the relationship between tool characteristics and their suitability for clinical scan repurposing.

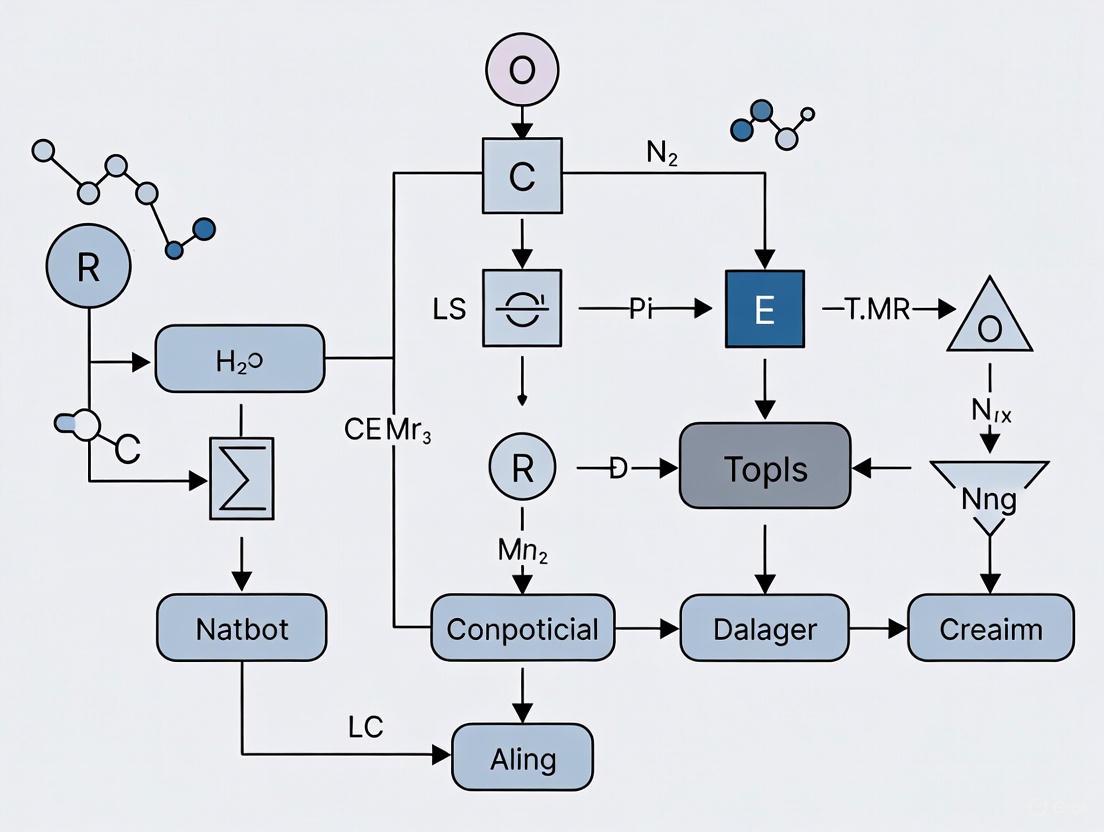

Diagram 1: Tool Benchmarking Workflow. This flowchart outlines the key steps for evaluating the reliability of segmentation tools on contrast-enhanced versus non-contrast MRI scans, from data input to final assessment.

Diagram 2: From Tool Robustness to Research Value. This diagram shows the logical relationship where a tool's robustness enables it to handle technical heterogeneity, which in turn unlocks the potential for repurposing clinical scans for research.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Software and Computational Tools for CE-MR Research

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function in Research | Notable Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| SynthSeg+ [1] [2] | Deep Learning Segmentation Tool | Brain structure volumetry from clinical scans | Contrast-agnostic; high reliability on CE-MR; handles variable resolutions [1] [2] |

| MindGlide [3] | Deep Learning Segmentation Tool | Brain and lesion volumetry from any single contrast | Processes T1, T2, FLAIR, PD; fast inference; validated for treatment effect detection [3] |

| CAT12 [1] [2] | MRI Segmentation Pipeline | Comparative traditional tool for brain morphometry | SPM-based; serves as a benchmark; shows limitations with CE-MR heterogeneity [1] [2] |

| ITK-SNAP [6] [7] | Software Application | Manual delineation and visualization of regions of interest (ROI) | Used for ground truth segmentation in training datasets [6] |

| PyRadiomics [6] | Python Library | Extraction of radiomic features from medical images | Enables texture and heterogeneity analysis beyond simple volumetry [6] |

| BRATS Dataset [4] | Benchmarking Dataset | Training and validation for brain tumor segmentation | Provides multi-modal MRI data with expert annotations [4] |

The technical heterogeneity of clinical CE-MR scans, once a significant barrier, can now be effectively mitigated by advanced deep learning segmentation tools. The comparative data indicates that models like SynthSeg+ and MindGlide, which are designed to be robust to variations in contrast and acquisition parameters, show high reliability and are particularly suited for repurposing clinical archives [1] [3]. In contrast, more traditional pipelines like CAT12 demonstrate inconsistent performance when applied to CE-MR data [1] [2].

The successful application of these tools in detecting treatment effects in clinical trials for conditions like multiple sclerosis validates their potential to unlock new insights from old scans [3]. This capability significantly broadens the pool of data available for retrospective research and drug development, potentially reducing the cost and time of clinical trials. Future developments will likely focus on further improving generalizability across all brain structures—particularly addressing current discrepancies in CSF and ventricular volumes—and integrating these tools into seamless, end-to-end analysis pipelines for both clinical and research environments. By leveraging these sophisticated tools, researchers can transform underutilized clinical MRI archives into a powerful resource for understanding brain structure and disease progression.

Automated brain volumetry is a cornerstone of modern neuroimaging research and clinical practice, essential for screening and monitoring neurodegenerative diseases. However, the reliability of these measurements across different software, scanner models, and scanning sessions remains a significant challenge. This comparison guide objectively evaluates the performance of leading brain segmentation tools amidst these sources of variability, with particular emphasis on their application to contrast-enhanced MR (CE-MR) scans. Understanding these factors is crucial for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals who rely on precise, reproducible volumetric measurements across multi-site studies and longitudinal clinical trials.

Quantitative Comparison of Segmentation Tools

Scan-Rescan Reliability of Volumetric Software

A comprehensive 2025 study systematically investigated the reliability of seven brain volumetry tools by analyzing scans from twelve subjects across six different scanners during two sessions conducted on the same day. The research evaluated measurements of gray matter (GM), white matter (WM), and total brain volume, providing critical insights into software performance variability [8].

Table 1: Scan-Rescan Reliability of Brain Volumetry Tools

| Segmentation Tool | Gray Matter CV (%) | White Matter CV (%) | Total Brain Volume CV (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| AssemblyNet | <0.2% | <0.2% | 0.09% |

| AIRAscore | <0.2% | <0.2% | 0.09% |

| FreeSurfer | >0.2% | >0.2% | >0.2% |

| FastSurfer | >0.2% | >0.2% | >0.2% |

| syngo.via | >0.2% | >0.2% | >0.2% |

| SPM12 | >0.2% | >0.2% | >0.2% |

| Vol2Brain | >0.2% | >0.2% | >0.2% |

The coefficient of variation (CV) data reveals striking differences in measurement consistency. AssemblyNet and AIRAscore demonstrated superior scan-rescan reliability with median CV values below 0.2% for gray and white matter, and exceptionally low 0.09% for total brain volume [8]. This high reproducibility makes them particularly valuable for longitudinal studies where detecting subtle changes over time is essential. In contrast, all other tools exhibited greater variability with CVs exceeding 0.2%, potentially limiting their sensitivity for tracking progressive neurological conditions.

Statistical analysis using generalised estimating equations models revealed significant main effects for both software (Wald χ² = 22377.50, df = 6, p < 0.001) and scanner (Wald χ² = 91.76, df = 5, p < 0.001) on gray matter volume measurements, but not for scanning session (Wald χ² = 1.47, df = 1, p = 0.23) [8]. This indicates that while immediate repeat scanning doesn't significantly affect measurements, the choice of software and scanner introduces substantial variability.

Performance on Contrast-Enhanced vs. Non-Contrast MRI

The ability to extract reliable morphometric data from contrast-enhanced clinical scans significantly expands research possibilities. A 2025 comparative study evaluated this capability using 59 normal participants with both T1-weighted CE-MR and non-contrast MR (NC-MR) scans [1].

Table 2: Segmentation Tool Performance on CE-MR vs. NC-MR

| Segmentation Tool | Reliability (ICC) | Structures with Discrepancies | Age Prediction Comparable |

|---|---|---|---|

| SynthSeg+ | >0.90 for most structures | CSF and ventricular volumes | Yes |

| CAT12 | Inconsistent performance | Multiple structures | No |

The deep learning-based SynthSeg+ demonstrated exceptional reliability, with intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) exceeding 0.90 for most brain structures when comparing CE-MR and NC-MR scans [1]. This robust performance confirms that modern deep learning approaches can effectively handle the intensity variations introduced by gadolinium-based contrast agents. Notably, age prediction models built using SynthSeg+ segmentations yielded comparable results for both scan types, further validating their equivalence for research purposes [1].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Multi-Scanner Reliability Assessment Protocol

The seminal scan-rescan reliability study employed a rigorous methodology to isolate variability sources [8]:

- Subject Cohort: Twelve healthy subjects (6 women, 6 men) with mean age 35.3 years (±8.5 years)

- Scanning Protocol: Examinations performed between March-November 2021 using six different scanners from the same vendor

- Temporal Design: Two separate scanning sessions conducted within 2 hours on the same day to minimize biological variation

- Software Evaluation: Seven volumetry tools tested, including both research tools and certified medical device software

- Statistical Analysis: Generalized estimating equations models to assess fixed effects of software, scanner, and session, with Wald χ² statistics and post-hoc analysis of interactions

This experimental design enabled researchers to quantify each variability source independently while controlling for biological changes that might occur between more widely spaced scanning sessions.

CE-MR Reliability Assessment Protocol

The contrast-enhanced MRI reliability study implemented this methodology [1]:

- Participants: 59 normal individuals aged 21-73 years, providing broad age representation

- Scan Types: Paired T1-weighted contrast-enhanced and non-contrast MR scans from each participant

- Segmentation Tools: CAT12 and SynthSeg+ for volumetric measurement extraction

- Analysis Approach: Intraclass correlation coefficients to quantify agreement between CE-MR and NC-MR measurements; age prediction models to validate clinical relevance

This protocol specifically addressed whether contrast administration fundamentally alters the ability to derive accurate morphometric measurements, a critical consideration for leveraging abundant clinical scans for research purposes.

Segmentation Reliability Workflow

The diagram below illustrates the key factors influencing segmentation reliability and their interactions, based on current research findings:

Segmentation Reliability Factors - This workflow illustrates how software, scanner, session, and contrast factors influence reliability metrics.

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Segmentation Reliability Studies

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Performance Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-Reliability Software | AssemblyNet, AIRAscore, SynthSeg+ | Automated brain volumetry | CV <0.2%, ICC >0.90 for most structures [8] [1] |

| Scanner Harmonization | Deep learning super-resolution (TCGAN) | Enhance 1.5T images to 3T quality | Reduces field strength variability [9] |

| Multi-Site Robust Algorithms | LOD-Brain (3D CNN) | Handle multi-site variability | Trained on 27,000 scans from 160 sites [10] |

| Quality Assessment Tools | Structural Similarity Index (SSIM), Coefficient of Variation | Quantify segmentation reliability | Detect protocol deviations [8] [11] |

| Contrast-Enhanced Processing | SynthSeg+ | Segment contrast-enhanced MRI | Maintains reliability vs non-contrast (ICC >0.90) [1] |

The evidence consistently demonstrates that software choice exerts the strongest influence on segmentation reliability, significantly outweighing effects from scanner differences or rescan sessions [8]. For research requiring high-precision longitudinal measurements, tools like AssemblyNet and AIRAscore provide superior reliability with CV values below 0.2% [8]. When working with contrast-enhanced clinical scans, deep learning-based approaches like SynthSeg+ maintain excellent reliability (ICC >0.90) compared to non-contrast scans [1].

To maximize segmentation reliability in research and drug development applications:

- Standardize Software Platforms: Use the same software tools throughout longitudinal studies and multi-site trials

- Leverage CE-MR Scans Confidently: Modern deep learning tools can reliably extract morphometric data from contrast-enhanced scans

- Implement Scanner Consistency: When possible, use the same scanner model and acquisition protocols across timepoints

- Adopt Harmonization Approaches: For multi-site studies, utilize algorithms specifically designed for cross-site reliability like LOD-Brain [10]

These strategies ensure that observed brain volume changes reflect genuine biological phenomena rather than technical variability, ultimately enhancing the validity and impact of neuroimaging research in both academic and clinical trial settings.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is indispensable in clinical and research settings for its exceptional soft-tissue contrast and detailed visualization of internal structures [12]. A fundamental parameter of any MRI system is its magnetic field strength, measured in Tesla (T), with 1.5T and 3T being the most prevalent field strengths in clinical use today [13] [14]. The choice between these field strengths carries significant implications for the quantitative volume measurements that are crucial for tracking disease progression in neurological disorders and for biomedical research [15] [16].

This guide objectively compares the performance of 1.5T and 3T MRI scanners, with a specific focus on their impact on the reliability of brain volume measurements derived from automated segmentation tools. As research and clinical diagnostics increasingly rely on precise, longitudinal volumetry, understanding the variability introduced by the imaging hardware itself is essential. This analysis is framed within broader investigations into the reliability of segmentation tools on contrast-enhanced MR (CE-MR) scans, providing researchers and drug development professionals with the data needed to inform their experimental designs and interpret their results accurately.

Technical Comparison: 1.5T vs. 3T MRI Scanners

The primary difference between 1.5T and 3T scanners is the strength of their main magnetic field. While a 3T scanner's magnet is twice as strong as a 1.5T's, the practical implications are complex and involve trade-offs between signal, artifacts, and safety [12].

Table 1: Core Technical Characteristics of 1.5T and 3T MRI Scanners

| Feature | 1.5T MRI | 3T MRI | Practical Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Magnetic Field Strength | 1.5 Tesla | 3.0 Tesla | The fundamental differentiating parameter. |

| Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) | Standard | Approximately twice that of 1.5T [17] [12] | Higher SNR at 3T can be used to increase spatial resolution or decrease scan time. |

| Spatial Resolution | Good for most clinical applications | Superior for visualizing small anatomical structures and subtle pathology [17] | 3T is advantageous for imaging small brain structures (e.g., hippocampal subfields). |

| Scan Time | Standard | Potentially faster for images of comparable quality [14] [12] | 3T can improve patient throughput and reduce motion artifacts. |

| Safety & Compatibility | Broader compatibility with medical implants [13] | More implants are unsafe or conditional at 3T; increased specific absorption rate (SAR) [13] [17] | Patient screening is more critical for 3T; may exclude some subjects from studies. |

| Artifacts | Lower susceptibility to artifacts (e.g., from chemical shift or metal) [12] | Increased susceptibility artifacts, particularly at tissue-air interfaces [17] [12] | Can affect image quality near the sinuses or temporal lobes, potentially confounding segmentation. |

| Cost & Infrastructure | Lower purchase, installation, and maintenance costs [14] | 25-50% higher purchase cost; may require more specialized site planning [14] | 1.5T is often more cost-effective and accessible. |

The increased SNR is the most significant advantage of 3T systems. It provides a foundation for higher spatial resolution, which is critical for delineating subtle neuroanatomy. However, this benefit is accompanied by challenges, including increased energy deposition in tissue (measured as SAR) and a greater propensity for image distortions due to magnetic susceptibility [17]. These factors must be carefully managed through sequence optimization.

Impact on Automated Volume Measurements

The variability introduced by changing magnetic field strength is a critical concern in longitudinal studies and multi-center trials where patients may be scanned on different systems. Evidence suggests that this variability can be significant and is handled differently by various segmentation software tools.

Key Experimental Findings on Measurement Variability

A 2024 study directly investigated this issue by comparing the reliability of two automated segmentation tools—FreeSurfer and Neurophet AQUA—across 1.5T and 3T scanners [15]. The study involved patients scanned at both field strengths within a six-month period. The results provide a quantitative basis for understanding measurement variability.

Table 2: Reliability of Volume Measurements Across Magnetic Field Strengths (1.5T vs. 3T)

| Brain Region | Segmentation Tool | Effect Size (1.5T vs. 3T) | Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) | Average Volume Difference Percentage (AVDP) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cortical Gray Matter | FreeSurfer | -0.307 to 0.433 | 0.869 - 0.965 | >10% |

| Neurophet AQUA | -0.409 to 0.243 | Not Specified | <10% | |

| Cerebral White Matter | FreeSurfer | Significant difference (p<0.001) | 0.965 | >10% |

| Neurophet AQUA | Significant difference (p<0.001) | Not Specified | <10% | |

| Hippocampus | FreeSurfer | Not Specified | Not Specified | >10% |

| Neurophet AQUA | Not Specified | Not Specified | <10% | |

| Amygdala | FreeSurfer | Significant difference (p<0.001) | 0.922 | >10% |

| Neurophet AQUA | Not Specified | Not Specified | <10% | |

| Thalamus | FreeSurfer | Significant difference (p<0.001) | 0.922 | >10% |

| Neurophet AQUA | Not Specified | Not Specified | <10% |

The study found that while both tools showed statistically significant volume differences for most brain regions between 1.5T and 3T, the effect sizes were generally small [15]. This indicates that the magnitude of the difference may not be biologically large. A key finding was that Neurophet AQUA yielded a smaller average volume difference percentage (AVDP) across all brain regions (all <10%) compared to FreeSurfer (all >10%) [15]. This suggests that some modern segmentation tools may be more robust to field strength-induced variability.

Furthermore, the study noted differences in the quality of segmentations; Neurophet AQUA produced stable connectivity without invading other regions, whereas FreeSurfer's segmentation of the hippocampus, for instance, sometimes encroached on the inferior lateral ventricle [15]. The processing time also differed dramatically, with Neurophet AQUA completing segmentations in approximately 5 minutes compared to 1 hour for FreeSurfer [15].

The Role of AI in Harmonizing Measurements

The challenge of field strength variability is being addressed through advanced AI and deep learning models. Research demonstrates that these tools can enhance the consistency of volumetric measurements across different scanner platforms.

One approach involves using generative models to improve data from lower-field systems. For example, the LoHiResGAN model uses a generative adversarial network (GAN) to enhance the quality and resolution of ultra-low-field (64mT) MRI images to a level comparable with 3T MRI [16]. Another model, SynthSR, is a convolutional neural network (CNN) that can generate synthetic high-resolution images from various input sequences, effectively mitigating variability caused by differences in scanning parameters [16]. Studies applying these models have shown that they can reduce systematic deviations in brain volume measurements acquired at different field strengths, bringing ultra-low-field estimates closer to the 3T reference standard [16].

The experimental workflow for such a harmonization analysis typically involves acquiring images from the same subjects on different scanner platforms, processing the data through these AI models, and then comparing the volumetric outputs to a reference standard.

Experimental Workflow for Cross-Field-Strength Analysis

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

For researchers designing studies involving volume measurements across different MRI field strengths, the following tools and software are essential.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Software Solutions

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function in Research | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| FreeSurfer | Automated Segmentation Software | Provides detailed segmentation of brain structures from MRI data. | Long processing time (~1 hr); shows higher volume variability with field strength (>10% AVDP) [15]. |

| Neurophet AQUA | Automated Segmentation Software | Provides automated brain volumetry with clinical approval. | Faster processing (~5 min); shows lower volume variability with field strength (<10% AVDP) [15]. |

| TotalSegmentator MRI | AI Segmentation Model (nnU-Net-based) | Robust, sequence-agnostic segmentation of multiple anatomic structures in MRI. | Open-source; trained on both CT and MRI data for improved generalization [18]. |

| DeepMedic | Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) | Used for specialized segmentation tasks, such as branch-level carotid artery segmentation in CE-MRA [19]. | Demonstrates the application of deep learning for complex vascular structures. |

| SynthSR & LoHiResGAN | Deep Learning Harmonization Models | Improve alignment and consistency of volumetric measurements from different field strengths, including ultra-low-field MRI [16]. | Key for mitigating scanner-induced variability in multi-center or longitudinal studies. |

The choice between 1.5T and 3T MRI systems presents a clear trade-off. 3T scanners offer higher SNR and spatial resolution, which can translate into superior visualization of fine anatomic detail and potentially faster scan times [17] [12]. However, this does not automatically guarantee more reliable volume measurements. The evidence indicates that changing the magnetic field strength introduces statistically significant variability in automated volume measurements, a factor that must be accounted for in study design [15].

The reliability of these measurements is not solely dependent on the scanner but is also a function of the segmentation tool used. Modern tools like Neurophet AQUA and AI harmonization models like SynthSR demonstrate that software can be engineered to be more robust to this underlying hardware variability [15] [16]. For researchers and drug development professionals, this underscores a critical point: rigorous study design must include a pre-planned strategy for managing cross-scanner variability, whether through consistent hardware use, sophisticated statistical correction, or the application of AI-powered harmonization tools to ensure that measured volume changes reflect biology rather than instrumentation.

In the evolving field of medical imaging, particularly with the rise of artificial intelligence (AI)-based analytical tools, scan-rescan reliability has emerged as a fundamental requirement for validating quantitative measurements. This reliability ensures that observed changes in longitudinal studies—such as monitoring neurodegenerative disease progression or treatment response—reflect true biological signals rather than methodological noise. For researchers utilizing contrast-enhanced MR (CE-MR) scans, understanding the performance characteristics of different segmentation software is crucial. This guide provides an objective comparison of various volumetry tools based on their scan-rescan reliability, quantified through the Coefficient of Variation (CV%) and Limits of Agreement (LoA), to inform selection for clinical and research applications.

Quantitative Comparison of Segmentation Tool Reliability

The reliability of automated brain volumetry software was directly assessed in a 2025 study that compared seven tools using scan-rescan data from twelve subjects across six scanners [8]. The following table summarizes the key reliability metrics for grey matter (GM), white matter (WM), and total brain volume (TBV) measurements.

Table 1: Scan-Rescan Reliability of Brain Volumetry Tools [8]

| Segmentation Tool | GM Median CV% | WM Median CV% | TBV Median CV% | Bland-Altman Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AssemblyNet | < 0.2% | < 0.2% | 0.09% | No systematic difference; variable LoA |

| AIRAscore | < 0.2% | < 0.2% | 0.09% | No systematic difference; variable LoA |

| FreeSurfer | > 0.2% | > 0.2% | > 0.2% | No systematic difference; variable LoA |

| FastSurfer | > 0.2% | > 0.2% | > 0.2% | No systematic difference; variable LoA |

| syngo.via | > 0.2% | > 0.2% | > 0.2% | No systematic difference; variable LoA |

| SPM12 | > 0.2% | > 0.2% | > 0.2% | No systematic difference; variable LoA |

| Vol2Brain | > 0.2% | > 0.2% | > 0.2% | No systematic difference; variable LoA |

The data demonstrates a clear performance tier. AssemblyNet and AIRAscore showed superior repeatability, with median CVs under 0.2% for GM and WM and 0.09% for TBV. In contrast, the other five tools exhibited higher variability, with CVs exceeding 0.2% for all tissue classes [8]. The Bland-Altman analysis confirmed an absence of systematic bias across all methods, but the width of the LoA varied significantly, indicating differences in measurement precision [8].

For studies involving contrast-enhanced MRI, the choice of segmentation software is equally critical. A 2025 comparative study found that the deep learning-based tool SynthSeg+ could reliably extract morphometric data from CE-MR scans, showing high agreement with non-contrast MR (NC-MR) scans for most brain structures (Intraclass Correlation Coefficients, ICCs > 0.90) [1]. Conversely, CAT12 demonstrated inconsistent performance in this context [1].

Experimental Protocols for Reliability Assessment

The comparative data presented above are derived from rigorous experimental designs. Below, we detail the core methodologies used in the cited studies to guide researchers in designing their own reliability assessments.

Protocol 1: Multi-Scanner, Multi-Software Brain Volumetry

This protocol evaluated the effect of scanner, software, and scanning session on brain volume measurements [8].

- Subjects: Twelve healthy subjects (6 women, 6 men; mean age 35.3 ± 8.5 years).

- Scanning: Each subject was scanned on six different MRI scanners from the same vendor during a single session, and then rescanned within two hours.

- Volumetry Tools: The T1-weighted images from both sessions were processed by seven automated brain volumetry tools: AssemblyNet, AIRAscore, FreeSurfer, FastSurfer, syngo.via, SPM12, and Vol2Brain.

- Statistical Analysis: The statistical analysis involved fitting Generalised Estimating Equations (GEE) models to quantify the effects of software, scanner, and session on GM, WM, and TBV volumes. Scan-rescan reliability was primarily assessed using the percentage of coefficient of variation (CV%). Bland-Altman analysis was used to evaluate agreement and calculate the limits of agreement (LoA) between scan and rescan measurements [8].

Protocol 2: Contrast-Enhanced vs. Non-Contrast MRI Volumetry

This protocol specifically assessed the reliability of morphometric measurements from CE-MR scans [1].

- Participants & Imaging: Fifty-nine normal participants underwent both T1-weighted CE-MR and NC-MR scans.

- Segmentation & Analysis: The scans were processed using two segmentation tools: CAT12 and SynthSeg+. Volumetric measurements for various brain structures were extracted from both scan types.

- Reliability Assessment: Agreement between measurements from CE-MR and NC-MR scans was quantified using Intraclass Correlation Coefficients (ICCs). The efficacy of the derived volumes was further tested by building age prediction models for both scan types [1].

Visualizing Reliability Assessment Workflows

The process of establishing scan-rescan reliability follows a structured pathway, from data acquisition to the final statistical interpretation. The diagram below outlines this general workflow, which is common to the experimental protocols described.

Figure 1: Generalized Scan-Rescan Reliability Workflow. The "Rescan" step is critical for assessing measurement variability independent of true biological change.

A significant finding from recent studies is that the variability in final measurements is not solely due to the imaging process itself. The analysis software introduces substantial variability, as illustrated below.

Figure 2: Software-Induced Variability in Volumetry. Identical input images processed with different software algorithms can yield outputs with significantly different reliability metrics, such as the Coefficient of Variation (CV%) [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key software tools and methodological components frequently employed in scan-rescan reliability research.

Table 2: Key Reagents and Solutions for Reliability Research

| Tool / Material | Type | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| AIRAscore | Automated Volumetry Software | Certified medical device software for brain volume measurement; demonstrates high scan-rescan reliability (CV < 0.2%) [8]. |

| SynthSeg+ | Deep Learning Segmentation Tool | Segments brain MRI scans without requiring retraining; shows high reliability (ICCs > 0.90) for contrast-enhanced MRI analysis [1]. |

| FreeSurfer | Neuroimaging Software Toolkit | A widely used, established academic tool for brain morphometry; used as a benchmark in comparative reliability studies [8]. |

| nnUNet | AI Segmentation Framework | An adaptive framework for automated medical image segmentation; used in developing models for complex structures like coronary arteries [20]. |

| ICC & CV% | Statistical Metrics | Quantifies reliability and agreement (ICC) and measures relative repeatability (CV%) for scan-rescan and inter-software comparisons [8] [21]. |

| Bland-Altman Analysis | Statistical Method | Assesses agreement between two measurement techniques by calculating the "limits of agreement" between scan and rescan results [8]. |

| Dice Similarity Coefficient (DSC) | Image Overlap Metric | Evaluates the spatial overlap between segmentations, often used to measure intra- and inter-observer consistency (e.g., manual vs. AI contours) [20]. |

The empirical data lead to a clear and critical recommendation for the research community: to ensure reliable and clinically valuable longitudinal observations, the same combination of scanner and segmentation software must be used throughout a study [8]. The choice between tools like AssemblyNet, which offers exceptional repeatability (CV < 0.2%), and more established platforms like FreeSurfer, can fundamentally impact the interpretability of results. Furthermore, for studies leveraging clinically acquired CE-MR scans, deep learning-based tools like SynthSeg+ provide a reliable pathway for volumetric analysis [1]. As quantitative imaging biomarkers become increasingly integral to diagnostics and clinical trials, a rigorous, metrics-driven understanding of scan-rescan reliability is not merely beneficial—it is indispensable.

Methodological Approaches: Leveraging Deep Learning for Reliable CE-MR Segmentation

The segmentation of structures from medical images, particularly Contrast-Enhanced Magnetic Resonance (CE-MR) scans, is a fundamental task in medical image analysis, supporting critical activities from diagnosis to treatment planning. For years, this domain was dominated by traditional image processing algorithms. However, the emergence of deep learning (DL) represents a potential paradigm shift, offering a fundamentally different approach to solving segmentation challenges. This guide provides an objective comparison of the performance between these two generations of technology, framing the analysis within broader research on the reliability of segmentation tools for CE-MR scans. We synthesize data from recent, peer-reviewed studies to offer researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals a clear, evidence-based perspective on the capabilities and limitations of each approach.

Understanding the Tools: A Technological Divide

The distinction between traditional and deep learning-based tools is not merely incremental; it represents a fundamental difference in philosophy and implementation.

Traditional Image Segmentation Tools rely on hand-crafted features and classical digital image processing techniques. These methods include:

- Thresholding: Converting images into binary maps based on pixel intensity values [22].

- Region-Based Segmentation: Grouping adjacent pixels with similar characteristics, often starting from "seed" points (e.g., region-growing, watershed algorithms) [22].

- Edge Detection: Identifying and classifying pixels that constitute edges within an image using filters like Canny edge detection [22].

- Clustering-Based Methods: Using unsupervised algorithms like K-means to group pixels with common attributes into segments [22].

These methods are generally interpretable and computationally efficient but often struggle with the complexity and noise inherent in biological images.

Deep Learning-Based Segmentation Tools use artificial neural networks with multiple layers to learn complex patterns and features directly from the data during a training process. The majority of modern medical image segmentation models are based on Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) [23]. A landmark architecture is the U-Net, which uses an encoder-decoder structure with "skip connections" to preserve detailed information lost during downsampling, making it particularly effective for medical images [22] [23]. These models learn to perform segmentation by analyzing large-scale annotated datasets, iteratively improving their parameters to minimize the difference between their predictions and expert-created "ground truth" labels [23].

The following diagram illustrates the core structural difference between a traditional pipeline and a deep learning model like U-Net.

Quantitative Performance Comparison

The theoretical advantages of deep learning are borne out by empirical evidence. The table below summarizes key performance metrics from recent studies across various clinical applications, using CE-MR scans or comparable MRI data.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Deep Learning vs. Traditional Tools Across Anatomical Regions

| Anatomical Region & Task | Tool / Method | Performance Metrics | Key Findings / Clinical Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lumbar Spine MRI (Pathology Identification) [24] | Deep Learning (RadBot) | Sensitivity: 73.3%Specificity: 88.4%Positive Predictive Value: 80.3%Negative Predictive Value: 83.7% | Distinguished presence of neural compression at a statistically significant level (p < .0001) from a random event distribution. |

| Rectal Cancer CTV (Mesorectal Target Contouring) [25] | Deep Learning (nnU-Net Segmentation) | Median Hausdorff Distance (HD): 9.3 mmClinical Acceptability: 9/10 contours | Outperformed registration-based deep learning models, particularly in mid and cranial regions, and was more robust to anatomical variations. |

| Rectal Cancer CTV (Mesorectal Target Contouring) [25] | Deep Learning (Registration-based Model) | Median Hausdorff Distance (HD): 10.2 mmClinical Acceptability: 3/10 contours | Less accurate and clinically acceptable than the segmentation-based nnU-Net approach. |

| Hippocampus (Volumetric Segmentation) [26] | Traditional (e.g., FreeSurfer, FIRST) | N/A (Qualitative Assessment) | Tendency to over-segment, particularly at the anterior hippocampal border. Generally more time-consuming and resource-intensive. |

| Hippocampus (Volumetric Segmentation) [26] | Deep Learning (e.g., Hippodeep, FastSurfer) | Strong correlation with manual volumes; able to differentiate diagnostic groups (e.g., Healthy, MCI, Dementia). | Emerged as "particularly attractive options" based on reliability, accuracy, and computational efficiency. |

| Brain Tumor (Glioma Segmentation) [23] | Deep Learning (U-Net based models) | N/A (State-of-the-Art Benchmark) | Winning models of the annual BraTS challenge since 2012 are consistently based on U-Net architectures, establishing DL as the state-of-the-art. |

A critical metric for segmentation overlap is the Dice Similarity Coefficient (DSC), which measures the overlap between the predicted segmentation and the ground truth. While not all studies report DSC, its loss function counterpart was central to a rectal cancer study, which found that a deep learning segmentation model (nnU-Net) outperformed a registration-based model [25]. Furthermore, deep learning models have demonstrated high consistency in volumetric segmentation when scans are conducted on the same MRI scanner, a crucial factor for longitudinal studies in drug development [27].

Analysis of Experimental Protocols

To critically appraise the data, it is essential to understand the methodologies that generated it. The following table outlines the experimental protocols from key studies cited in this guide.

Table 2: Experimental Protocols from Key Cited Studies

| Study Reference | Imaging Data | Ground Truth Definition | Model Training & Evaluation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lumbar Spine Analysis [24] | - 65 lumbar MRI scans (383 levels)- Average age: 42.2 years | MRI reports from board-certified radiologists. Pathologies were extracted and categorized (e.g., no stenosis, stenosis). | - DL model (RadBot) analysis compared to radiologist's report.- Metrics: Sensitivity, Specificity, PPV, NPV.- Reliability: Cronbach alpha and Cohen's kappa calculated. |

| Rectal Cancer Contouring [25] | - 104 rectal cancer patients.- T2-weighted planning and daily fraction MRI from 1.5T/3T scanners. | Manually delineated mesorectal Clinical Target Volume (CTV) by a radiation oncologist, adjusted as needed for daily fractions. | - Model: 3D nnU-Net for segmentation.- Data Split: 68/14/22 (Train/Val/Test).- Loss Function: Cross-entropy + Soft-Dice loss.- Metrics: Hausdorff Distance (HD), Dice, qualitative clinical score. |

| Hippocampal Segmentation [26] | - 3 datasets (ADNI HarP, MNI-HISUB25, OBHC) with manual labels.- Included Healthy, MCI, and Dementia patients. | Manual segmentation following harmonized protocols (e.g., HarP) considered the gold standard. | - Evaluation: 10 automatic methods (Traditional & DL) compared.- Metrics: Overlap with manual labels, volume correlation, group differentiation, false positive/negative analysis. |

| Brain Tumor Segmentation [23] | - Public datasets from BraTS challenges.- Multi-institutional, multi-scanner MRI of gliomas, metastases, etc. | Expert-annotated tumor sub-regions (e.g., enhancing tumor, edema, necrosis). | - Models (typically U-Net variants) trained on large public datasets.- Performance benchmarked annually via the BraTS challenge. |

A common strength across these deep learning protocols is the use of a validation set to tune hyperparameters and a held-out test set to provide an unbiased estimate of model performance [25] [26]. Furthermore, the use of data from multiple sites and scanners [24] [26] helps to stress-test the generalizability of the models, a vital consideration for clinical and multi-center research applications.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

For researchers aiming to implement or evaluate these segmentation tools, the following table lists key "research reagents" and their functions.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Segmentation Tool Research

| Item / Solution | Function & Application in Research |

|---|---|

| Annotated Datasets (e.g., BraTS, ADNI) | Provide the essential "ground truth" labels for training supervised deep learning models and for benchmarking the performance of both traditional and DL tools [23] [26]. |

| Deep Learning Frameworks (e.g., PyTorch, TensorFlow) | Open-source libraries that provide the foundational building blocks and computational graphs for designing, training, and deploying deep neural networks. |

| Specialized Segmentation Frameworks (e.g., nnU-Net) | An out-of-the-box framework that automatically configures the network architecture and training procedure based on the dataset properties, often achieving state-of-the-art results without manual tuning [25]. |

| Traditional Algorithm Suites (e.g., in OpenCV, ITK) | Software libraries containing implementations of classic image segmentation algorithms like thresholding, region-growing, and clustering, used for baseline comparisons or specific applications [22]. |

| Performance Metrics (Dice, Hausdorff Distance, Sensitivity/Specificity) | Quantitative measures that objectively evaluate and compare the accuracy, overlap, and clinical utility of different segmentation methods [24] [25] [23]. |

| Compute Infrastructure (GPU Acceleration) | High-performance computing hardware, particularly GPUs, which are critical for reducing the time required to train complex deep learning models on large medical image datasets [28] [25]. |

The evidence from recent and rigorous studies indicates that a performance paradigm shift is underway. While traditional segmentation tools maintain utility for specific, well-defined tasks, deep learning has established a new benchmark for accuracy, automation, and scalability in the analysis of CE-MR scans.

Deep learning models consistently demonstrate superior performance in complex segmentation tasks across neurology, oncology, and musculoskeletal imaging [24] [25] [23]. They show a enhanced ability to identify clinically relevant features and, crucially, integrate into workflows where efficiency is paramount. However, this power comes with demands for large, high-quality annotated datasets and significant computational resources. For the research and drug development community, the choice is no longer about whether deep learning is more powerful, but about how to best leverage its capabilities while managing its requirements for robust and reliable outcomes.

Clinical brain MRI scans, including contrast-enhanced (CE-MR) images, represent a vast and underutilized resource for neuroscience research [2]. The variability in acquisition protocols, particularly the use of gadolinium-based contrast agents, presents a significant challenge for automated segmentation tools, which are essential for quantitative morphometric analysis. Traditionally, convolutional neural networks (CNNs) have demonstrated high sensitivity to changes in image contrast and resolution, often requiring retraining or fine-tuning for each new domain [29]. This technical heterogeneity has limited the large-scale analysis of clinically acquired CE-MR scans.

Within this context, tools demonstrating contrast invariance are of paramount importance. SynthSeg emerged as a pioneering CNN for segmenting brain MRI scans of any contrast and resolution without retraining [29] [30]. Its enhanced successor, SynthSeg+, was specifically designed for increased robustness on heterogeneous clinical data, including scans with low signal-to-noise ratio or poor tissue contrast [31] [32]. This guide provides a detailed examination of SynthSeg+'s architecture, benchmarks its performance against alternative tools, and presents experimental data validating its reliability for analyzing CE-MR scans, thereby unlocking their potential for research.

Architectural Innovation of SynthSeg+

Core Framework and Domain Randomization

The foundation of SynthSeg's robustness is a domain randomisation strategy trained with synthetic data [29] [33]. Unlike supervised CNNs trained on real images of a specific contrast, SynthSeg is trained exclusively on synthetic data generated from a generative model conditioned on anatomical segmentations.

- Synthetic Data Generation: The model creates synthetic images by sampling intensities for each anatomical structure from a Gaussian Mixture Model (GMM). Crucially, generation parameters—including image contrast and resolution—are fully randomized for each minibatch from uninformative uniform priors [29] [34].

- Training Process: By exposing the network to an extremely wide and unrealistic range of image appearances, it is forced to learn domain-agnostic features tied to anatomical shape and context rather than specific intensity profiles [33]. This enables the single trained model to segment real scans from a wide range of target domains, including different MR contrasts and even CT, without retraining [29] [32].

The SynthSeg+ Hierarchy for Enhanced Robustness

While SynthSeg is generally robust, it can falter on clinical scans with very low signal-to-noise ratio or poor tissue contrast [31]. SynthSeg+ introduces a novel, hierarchical architecture to mitigate these shortcomings.

As illustrated in the diagram below, SynthSeg+ employs a sequence of networks, each conditioned on the output of the previous one, to progressively refine the segmentation.

This hierarchical workflow functions as follows:

- Initial Segmentation (

S1): The first segmentation network processes the raw, potentially noisy input scan to produce an initial segmentation estimate [31]. - Denoising (

D): A dedicated denoising network then takes the initial segmentation and the original input image. It generates a "cleaner," denoised version of the segmentation, which helps suppress errors and inconsistencies [31]. - Refined Segmentation (

S2): A second segmentation network, identical in architecture to the first, takes the original input image and the denoised segmentation from the previous step. Conditioned on this improved prior,S2produces the final, refined segmentation output [31].

This multi-stage, conditional pipeline proves considerably more robust than the original SynthSeg, outperforming both cascaded networks and state-of-the-art segmentation denoising methods on challenging clinical data [31].

Performance Benchmarking in CE-MR Analysis

Comparative Reliability on CE-MR vs. Non-Contrast MR

A pivotal 2025 study by Aman et al. directly evaluated the reliability of brain volumetric measurements from CE-MR scans compared to non-contrast MR (NC-MR) scans, using both SynthSeg+ and the CAT12 segmentation tool [2] [1].

Table 1: Comparative Reliability of Volumetric Measurements between CE-MR and NC-MR Scans

| Brain Structure Category | SynthSeg+ (ICC) | CAT12 (ICC) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Most Brain Structures | > 0.90 [2] | Inconsistent [2] | SynthSeg+ showed high reliability for most regions, with larger structures having ICC > 0.94 [2]. |

| Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF) & Ventricles | Discrepancies noted [2] | Inconsistent [2] | |

| Thalamus | Slight overestimation in CE-MR [2] | Inconsistent [2] | |

| Brain Stem | Robust correlation (lowest among high ICCs) [2] | Inconsistent [2] |

The experimental protocol for this benchmark was as follows:

- Dataset: 59 paired T1-weighted CE-MR and NC-MR scans from clinically normal individuals (age range 21-73 years) [2].

- Methodology: Each scan was processed through both SynthSeg+ and CAT12 segmentation tools. The resulting volumetric measurements for multiple brain structures were then compared between CE-MR and NC-MR scans for each tool [2].

- Outcome Measurement: Reliability was quantified using Intraclass Correlation Coefficients (ICCs). The study also constructed age prediction models to assess the utility of the volumetric measurements from both scan types [2].

The conclusion was clear: "Deep learning-based approaches, particularly SynthSeg+, can reliably process contrast-enhanced MRI scans for morphometric analysis, showing high consistency with non-contrast scans across most brain structures" [2]. This finding significantly broadens the potential for using clinically acquired CE-MR images in neuroimaging research.

Generalizability Across Modalities and Populations

The robustness of the SynthSeg framework extends beyond CE-MR. The following table summarizes its validated performance across various imaging domains and subject populations.

Table 2: Generalizability of SynthSeg/SynthSeg+ Across Domains

| Domain | Performance | Key Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| CT Scans | Good segmentation performance, though with lower precision than MRI (Median Dice: 0.76) [35]. Suitable for applications where high precision is not essential [35]. | Validation on 260 paired CT-MRI scans from radiotherapy patients; able to replicate known morphological trends related to sex and age [35]. |

| Infant Brain MRI | Infant-SynthSeg model shows consistently high segmentation performance across the first year of life, enabling a single framework for longitudinal studies [34]. | Addresses large contrast changes and heterogeneous intensity appearance in infant brains; outperforms a traditional contrast-aware nnU-net in cross-age segmentation [34]. |

| Abdominal MRI | ABDSynth (a SynthSeg-based model) provides a viable alternative when annotated MRI data is scarce, though slightly less accurate than models trained on real MRI data [5]. | Trained solely on widely available CT segmentations; benchmarked on multi-organ abdominal segmentation across diverse datasets [5]. |

Practical Research Toolkit

Key Research Reagent Solutions

For researchers aiming to utilize SynthSeg+ for CE-MR analysis, the following tools and resources are essential.

Table 3: Essential Materials and Resources for SynthSeg+ Research

| Item/Resource | Function/Description | Availability |

|---|---|---|

| SynthSeg+ Model | The core deep learning model for robust, contrast-agnostic brain segmentation, including cortical parcellation and QC [33] [32]. | Integrated in FreeSurfer (v7.3.2+); available as a standalone Python package on GitHub [33] [32]. |

| Clinical CE-MR Datasets | Retrospective paired or unpaired CE-MR and NC-MR scans for validation and analysis studies [2]. | Hospital PACS systems, public repositories (e.g., ADNI [29]). |

| High-Performance Computing (CPU/GPU) | Runs SynthSeg+ on GPU (~15s/scan) or CPU (~1min/scan) [33]. | Local workstations or high-performance computing clusters. |

| FreeSurfer Suite | Provides the mri_synthseg command and environment for running the tool, along with visualization tools like Freeview [32]. |

FreeSurfer website. |

| Quality Control (QC) Scores | Automated scores assessing segmentation reliability for each scan, crucial for filtering data in large-scale studies [31] [32]. | Generated automatically by SynthSeg+ and saved to a CSV file. |

Implementation Workflow

The typical workflow for deploying SynthSeg+ in a research analysis, particularly for CE-MR scans, is outlined below.

This workflow involves:

- Data Acquisition: Gathering a heterogeneous set of clinical scans, which can include CE-MR images of varying resolutions and protocols [2] [31].

- Minimal Preprocessing: A key advantage of SynthSeg+ is that it requires no mandatory preprocessing (e.g., bias field correction, skull stripping), making it ideal for uncurated data [33] [32].

- Running SynthSeg+: The tool is executed, preferably using the

--robustflag for clinical data. It outputs segmentations at 1mm isotropic resolution and can simultaneously generate volumetric data and QC scores [32]. - Quality Control: The automated QC scores are used to identify and potentially exclude unreliable segmentations, ensuring the integrity of the downstream analysis [31] [35].

- Final Analysis: The robust volumetric measurements are used for morphometric analysis, enabling large-scale studies on clinical datasets [2] [31].

SynthSeg+ represents a significant leap forward in the analysis of clinically acquired brain MRI scans. Its hierarchical architecture, built upon a foundation of domain randomization, provides unparalleled robustness against the technical heterogeneity that has historically plagued clinical neuroimaging research. Experimental data confirms its superior reliability for volumetric analysis of contrast-enhanced MR scans compared to other tools like CAT12, closely replicating measurements from non-contrast scans [2]. Furthermore, its generalizability across modalities—from CT to infant MRI—demonstrates the power of its underlying framework [34] [35].

For researchers and drug development professionals, SynthSeg+ offers a practical and powerful solution for leveraging large, heterogeneous clinical datasets. By enabling consistent and accurate segmentation across diverse acquisition protocols and patient populations, it paves the way for large-scale, retrospective studies with sample sizes previously difficult to achieve, ultimately accelerating discoveries in neuroscience and clinical therapy development.

In the realm of neuroimaging research, particularly in studies involving contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance (CE-MR) scans, the reliability of automated segmentation tools is paramount. The foundation for any robust segmentation pipeline lies in its preprocessing steps, with skull stripping and intensity normalization being two critical components. These processes directly impact the quality and consistency of downstream analyses, including volumetric measurements, tissue classification, and pathological assessment. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, selecting the appropriate preprocessing tools is not merely a technical choice but a determinant of the validity and reproducibility of experimental outcomes. This guide provides an objective comparison of contemporary methodologies, underpinned by experimental data, to inform the development of a reliable preprocessing pipeline for CE-MR research.

Skull Stripping Performance Comparison

Skull stripping, or brain extraction, is the process of removing non-brain tissues such as the skull, scalp, and meninges from MR images. Its accuracy is crucial, as residual non-brain tissues can lead to significant errors in subsequent segmentation and analysis.

Quantitative Performance of Skull Stripping Tools

A comprehensive evaluation of state-of-the-art skull stripping tools reveals notable differences in their performance across diverse datasets. The following table summarizes key quantitative metrics from recent large-scale validation studies.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Modern Skull Stripping Tools

| Tool Name | Methodology | Primary Strength | Reported Dice Score | Key Limitation(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LifespanStrip [36] | Atlas-powered deep learning | Exceptional accuracy across lifespan (neonatal to elderly) | ~0.99 (on lifespan data) | Complex framework requiring atlas registration |

| SynthStrip [36] [37] | Deep learning trained on synthetic data | High generalizability across contrasts and resolutions | ~0.98 (on diverse data) | Slight under-segmentation in vertex region [36] |

| HD-BET [36] | Deep learning trained on multi-center data | Optimized for clinical neuro-oncology data | ~0.98 (on adult brains) | Subtle under-segmentation; struggles with infants [36] |

| ROBEX [36] | Hybrid generative-discriminative model | Robustness for adult brain imaging | <0.98 (lower on infants) | Noticeable under-segmentation in skull vertex [36] |

| FSL-BET [36] [37] | Deformable surface model | Speed and simplicity | <0.98 (varies with parameters) | Prone to over-segmentation at skull base [36] |

| 3DSS [36] | Hybrid surface-based method | Incorporates exterior tissue context | <0.98 | Over-segmentation in neck/face regions [36] |

| EnNet [38] | 3D CNN for multiparametric MRI | Superior performance on pathological (GBM) brains | ~0.95 (on GBM data) | Designed for mpMRI; performance may vary with single modality |

Experimental Protocols for Skull Stripping Evaluation

The quantitative data in Table 1 is derived from rigorous experimental protocols. A representative large-scale evaluation involved a dataset of 21,334 T1-weighted MRIs from 18 public datasets, encompassing a wide lifespan (neonates to elderly) and various scanners and imaging protocols [36]. The performance was primarily measured using the Dice Similarity Coefficient (Dice Score), which quantifies the spatial overlap between the tool-generated brain mask and a manually refined ground truth mask. A score of 1 indicates perfect overlap.

Another study focused on pathological brains, using a dataset of 815 cases with and without glioblastoma (GBM) from the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center and The Cancer Imaging Archive (TCIA) [38]. Ground truths were verified by qualified radiologists, and evaluation metrics included Dice Score and the 95th percentile Hausdorff Distance (measuring boundary accuracy).

Analysis and Recommendations

The data indicates that deep learning-based tools like LifespanStrip, SynthStrip, and HD-BET generally outperform conventional tools like BET and 3DSS, particularly in handling data heterogeneity [36]. The choice of tool, however, should be guided by the specific research context:

- For lifespan studies involving neonates, infants, or elderly populations, LifespanStrip is highly recommended due to its consistent performance driven by age-specific atlas priors [36].

- For studies with diverse MRI protocols or limited computational resources, SynthStrip presents a robust and generalizable option [36] [37].

- For neuro-oncology research involving brain tumors, tools like EnNet (if multiparametric MRI is available) or HD-BET are more appropriate, as they are validated on pathological brains where tissue appearance and boundaries are altered [38].

It is critical to note that all tools can exhibit failure modes. For example, several methods show consistent under- or over-segmentation in regions like the skull vertex, forehead, and skull base [36]. Furthermore, a recent study highlighted that skull-stripping itself can induce "shortcut learning" in deep learning models for Alzheimer's disease classification, where models may learn to rely on preprocessing artifacts (brain contours) rather than genuine pathological features [39]. This underscores the necessity of visual inspection and quality control after automatic skull stripping.

Intensity Normalization Techniques

Intensity normalization standardizes the voxel intensity ranges across different images, mitigating scanner-specific variations and improving the reliability of radiomic features and tissue segmentation.

Common Normalization Techniques

Unlike skull stripping, intensity normalization often involves simpler mathematical operations, but their selection and application are equally critical.

Table 2: Common Intensity Normalization Techniques in MRI

| Technique | Methodology | Use Case | Effect on Data |

|---|---|---|---|

| Z-score Normalization [40] | Scales intensities to have a mean of 0 and standard deviation of 1. | General-purpose; often used before deep learning model input. | Removes global offset and scales variance; assumes Gaussian distribution. |

| White Matter Peak-based Normalization [41] [39] | Normalizes intensities to the peak of the white matter tissue histogram. | Tissue-specific studies; common in structural T1w analysis. | Anchors intensities to a biologically relevant reference point. |

| Histogram Matching | Transforms the intensity histogram of an image to match a reference histogram. | Standardizing multi-site data to a common appearance. | Can be powerful but depends on the choice of a suitable reference. |

| Kernel Density Estimation (KDE) [41] | A data-driven approach for modeling the intensity distribution without assuming a specific shape. | Handling non-standard intensity distributions. | More flexible than parametric methods for complex distributions. |

Experimental Evidence and Protocols

The effect of intensity normalization was systematically investigated in a study on breast MRI radiomics. The research found that the application of normalization techniques significantly improved the predictive power of machine learning models for pathological complete response (pCR), especially when working with heterogeneous imaging data [41]. A key finding was that the benefit of normalization was more pronounced with smaller training datasets, suggesting it is a vital step when data is limited [41].

In a deep learning study for predicting brain metastases, a comprehensive preprocessing pipeline was implemented where MRI scans underwent skull stripping using SynthStrip followed by intensity normalization via Z-score normalization [40]. This combination contributed to the model's strong robustness and generalizability across internal and external validation sets.

A typical protocol for intensity normalization involves:

- Skull Stripping: This is often a prerequisite to ensure that intensity statistics are computed only from brain tissues [40].

- Background Exclusion: Voxels outside the brain mask are ignored.

- Statistical Calculation: Compute the chosen statistics (e.g., mean, standard deviation, white matter peak) from the voxels within the brain mask.

- Transformation: Apply the linear or non-linear transformation to all voxels in the image.

Integrated Preprocessing Workflow

For optimal results in segmenting CE-MR scans, skull stripping and intensity normalization should be implemented as part of a cohesive pipeline. The following diagram illustrates a recommended workflow and its logical rationale.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Software

Building a robust preprocessing pipeline requires both data and software tools. The following table details key "research reagents" – essential datasets and software solutions used in the field.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Preprocessing Pipeline Development

| Item Name | Type | Function/Benefit | Example Use in Cited Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Public Datasets (ADNI, dHCP, ABIDE) [36] | Data | Provide large-scale, diverse, multi-scanner MRI data for training and validation. | Used for large-scale evaluation of LifespanStrip across 21,334 scans [36]. |

| Pathological Datasets (TCIA-GBM) [38] | Data | Provide expert-annotated MRIs with pathologies like glioblastoma for domain-specific testing. | Used to train and validate EnNet on pre-/post-operative brains with GBM [38]. |

| FSL (FMRIB Software Library) [39] [37] | Software Suite | Provides a wide array of neuroimaging tools, including BET for skull stripping and FLIRT/FNIRT for registration. | Used for reorientation (FSL-REORIENT2STD) and non-linear registration (FSL-FNIRT) [39]. |

| FreeSurfer [42] [36] | Software Suite | Provides a complete pipeline for cortical reconstruction and volumetric segmentation, including skull stripping. | Used as a benchmark in comparative studies of skull stripping and volumetric reliability [42] [36]. |

| Advanced Normalization Tools (ANTs) | Software | Provides state-of-the-art image registration and bias field correction (e.g., N4). | Used for bias field correction in multiple studies [39]. |

| Python-based Libraries (SimpleITK, SciPy) [37] | Software Libraries | Offer flexibility for implementing custom preprocessing steps, scripting pipelines, and data analysis. | Integrated into a pediatric processing framework for tasks like registration and normalization [37]. |

The reliability of segmentation tools in CE-MR research is fundamentally tied to the preprocessing pipeline. Evidence indicates that deep learning-based skull stripping tools like LifespanStrip and SynthStrip offer superior accuracy and generalizability compared to conventional methods, especially for heterogeneous data. For intensity normalization, techniques like Z-score and white matter peak-based normalization are essential for standardizing data and improving model robustness. The experimental data consistently shows that the choice of software introduces significant variance in results [42]. Therefore, to ensure reliable and reproducible outcomes, researchers must carefully select their preprocessing tools based on their specific data characteristics—such as patient age, pathology, and imaging protocol—and maintain consistency in the software used throughout a study.

The precise segmentation of brain metastases (BMs) on contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance (CE-MR) images is a critical step in diagnostics and treatment planning, directly influencing patient outcomes in stereotactic radiotherapy and surgical interventions [43] [44] [45]. Manual segmentation by clinicians is often time-consuming, labor-intensive, and subject to inter-observer variability, creating a significant bottleneck in clinical workflows [46] [43]. This case study explores the successful application of 3D U-Net-based deep learning models to automate the segmentation of brain metastases, objectively comparing their performance against manual methods and other alternatives. We situate this analysis within a broader thesis on the reliability of different segmentation tools for CE-MR research, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a detailed comparison of experimental protocols, performance data, and practical implementation resources.

Performance Comparison of Segmentation Models

The evaluation of automated segmentation models relies on standardized quantitative metrics that measure the overlap between automated and manual expert segmentations (the reference standard), as well as the physical distance between their boundaries.

Table 1: Key Performance Metrics for Segmentation Model Evaluation

| Metric | Full Name | Interpretation | Ideal Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| DSC | Dice Similarity Coefficient | Measures volumetric overlap between segmentation and ground truth. | 1.0 (Perfect Overlap) |

| IoU | Intersection over Union | Similar to DSC, measures spatial overlap. | 1.0 (Perfect Overlap) |

| HD95 | 95th Percentile Hausdorff Distance | Measures the 95th percentile of the maximum boundary distances, robust to outliers. | 0 mm (No Distance) |

| ASD | Average Surface Distance | Average of all distances between points on the predicted and ground truth surfaces. | 0 mm (No Distance) |

| AUC | Area Under the ROC Curve | Measures the model's ability to distinguish between lesion and non-lesion areas. | 1.0 (Perfect Detection) |

Table 2: Comparative Performance of 3D U-Net Models for Brain Metastasis Segmentation

| Study (Model) | Dataset | Primary Metric (DSC) | Other Key Metrics | Inference Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bousabarah et al. [44] (Standard 3D U-Net) | Multicenter; 348 patients | 0.89 ± 0.11 (per metastasis) | F1-Score (Detection): 0.93 ± 0.16 | Not Specified |

| BUC-Net [43] (Cascaded 3D U-Net) | Single-center; 158 patients | 0.912 (Binary Classification) | HD95: 0.901 mm; ASD: 0.332 mm; AUC: 0.934 | < 10 minutes per patient |

| 3D U-Net (ResNet-34) [46] | Multi-institutional; 642 patients | AUC: 0.82 (Lung Cancer), 0.89 (Other Cancers) | Specificity: 1.000 across subgroups | 66-69 seconds vs. 96-113s (Manual) |

| MEASegNet [47] (3D U-Net with Attention) | Public (BraTS2021) | 0.845 (Enhancing Tumor) | Not directly comparable (focus on primary tumors) | Not Specified |

The data reveals that 3D U-Net variants achieve high segmentation accuracy, with DSCs exceeding 0.89, indicating excellent volumetric agreement with expert manual contours [43] [44]. The high F1-score of 0.93 further confirms their effectiveness in the detection task, minimizing both false positives and false negatives [44]. A significant finding is the cancer-type dependency of model performance; one study reported a statistically significant lower AUC for metastases from lung cancer (0.82) compared to other primary cancers (0.89), highlighting the need for sensitivity optimization in specific clinical subpopulations [46]. Crucially, all developed models maintain perfect specificity (1.000), meaning they reliably exclude non-metastatic tissue, which is vital for clinical safety [46]. From an efficiency standpoint, these models offer a substantial reduction in processing time, with one model completing segmentation in approximately one minute—about 40-50% faster than manual annotation—freeing up expert time for other critical tasks [46] [43].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Understanding the methodology is key to evaluating the reliability and reproducibility of these models. The following sections detail the standard experimental protocols used in the cited research.

Data Curation and Preprocessing

A rigorous and standardized preprocessing pipeline is fundamental to developing robust models.

- Patient Selection and Imaging: Studies typically use retrospective data from patients with confirmed brain metastases. The primary imaging modality is contrast-enhanced T1-weighted 3D MRI (e.g., 3D T1-weighted fast field echo or magnetization-prepared rapid gradient-echo sequences). Standard inclusion criteria involve adult patients (≥18 years) with complete clinical data and high-quality, artifact-free MRI scans [46] [43].

- Ground Truth Delineation: The reference standard for training and evaluation is established by manual segmentation performed by experienced radiologists or radiation oncologists (often with 8+ years of experience). Lesions are meticulously outlined on CE-MRI slices, with a third senior expert often consulted to resolve disagreements, ensuring high-quality ground truth [46] [43] [44].

- Image Preprocessing: A multi-step pipeline is employed:

- Resampling: Images are resampled to an isotropic voxel size (e.g., 0.833 mm³) to standardize spatial resolution [46].